Third Year In: A Young Farmer’s Thoughts

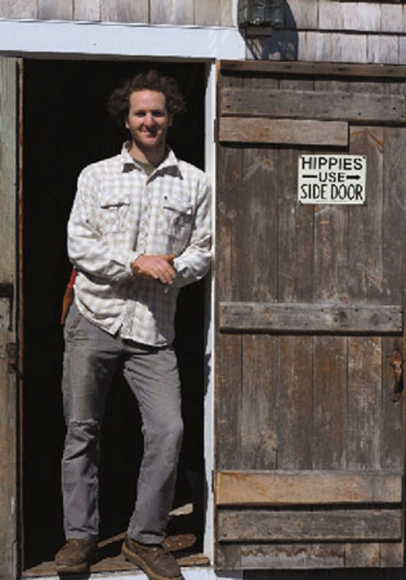

As Lucas Dinwiddie strides across the one-acre property he’s named Halcyon Farm, it’s clear to see it’s a sanctuary he loves.

The care he’s given to its design is plain. Paths are laid intentionally, fences and retaining walls are thoughtfully crafted, and composting and harvesting areas are composed for meaningful work. “My main objective is to leave no space left unplanted,” he says. “Even if it’s just a 10′ x 10′ planting bed, or a zone designated for a one-year cover crop of clover, I’m trying to use all the land.”

It’s a rare day in any month that Dinwiddie is not involved in finessing a solution to some challenge on his farm. If he doesn’t see the answer at first, he walks and observes and walks some more, until, he says, “I get a total epiphany.”

Coming into spring it’s time to see if the mountain of winter hours spent on planning for the next growing season “Stick or go out the window,” as Dinwiddie puts it. “Sometimes on paper it’s fine, but the soil’s too full of debris and not ready for planting, or the weather blows it. Every year has its own temperament; 2010 was really dry, and 2011 was amazingly cool.”

Especially now with the weather extremes much of the globe is experiencing, Dinwiddie finds the role of farmers who grow organically that much more important. “You just can’t put all those eggs in a single basket and grow one thing. It underscores the importance of a diversity of crops.”

Halcyon Farm’s offerings number about a dozen items, and fall into a few basic themes: salad greens, braising greens and roots, with a smattering of others like tomatoes and peas thrown in. “While I grow a lot more than one thing, I want to concentrate on what I can do well here on the Cape, and not do thirty varieties of each crop,” says Dinwiddie. He looks to the life experience of Eliot Coleman, a contemporary Maine farmer and writer. “I try to take out as many of the questions as I can, and master the growing of what I choose to raise. It shouldn’t be such hard work.”

Yet it is.

Dinwiddie acknowledges that in the prime-growing season his days seem to never end. “It would be nice if this year I could get a student to intern with me on the planting, the harvests and the composting.” Someday he muses that he may even have a good-sized crew of several paid employees working alongside him.

Last winter Dinwiddie managed some off-Cape travel time, but this year finds him laying low to accomplish projects on the farm. “I built a bunch of good-sized tables for seedlings, and now I’m incorporating refrigeration into one of my outbuildings.” A cooling unit will afford Dinwiddie a post-harvest storage facility, allowing greater windows of time for gathering produce and ensuring customers of the highest quality at his roadside stand. If the forecast is for torrential rain the day before a market, Dinwiddie is psyched that he will be able to harvest earlier and dodge the nasty weather.

“It’s hard being your own boss, but I can’t imagine any other life. I’m blessed with a family that’s supported me,” says Dinwiddie. “But can I make a living at it is the question. Define living, and for a single thirty-year old’s needs, probably yes,” he says. “You’d better be passionate about it though.”

“Most Cape farmers I know do a range of things to supplement their incomes, including photography, honey, eggs and the like, to name a few,” says Dinwiddie.

“There are lots of other places in America where smart young people are eager to be farmers and are succeeding at growing vegetables, but here, not so many.” Dinwiddie pauses, suddenly quiet, reflecting on the loss of two friends, Julie Winslow and Ron Caffoni, who died within the past year and were dedicated local growers.

“On the Cape, is it possible to take an acre of non-farming land—mine was sand—and transform it to a small market farm? I’m proving that it’s going to take a lot of work, and about five years, but it’s doable. One of the biggest objectives for me is documenting the process,” says Dinwiddie, a goal he’s in line with so far. Summer of 2012 will be his third summer of growing, and will edge him past the halfway point of his overall plan.

“The community of Brewster has been super-supportive of agriculture,” says Dinwiddie. “By-laws and special permits in this town have made it easier for small-scale farmers to succeed.” He anticipates becoming more involved with the Brewster Agricultural Commission, and also hopes to offer some spring planting workshops to the public.

The passionate response to his offerings at local markets is great. “There’s a line waiting for us to open on Saturday mornings,” he says, smiling. “It’s fun—it’s almost as if your face is on the produce—you’re growing it and you put it right into the buyer’s hands.”

“A few people are trying small-scale farming here,” he says, noting a pair of friends who are enthusiastically homesteading in Orleans, as well as Marie Norgeot who grows at Checkerberry Farm in the same town. Norgeot is farming in the path forged by her mother Gretel, who has supplied the community with vegetables and her renowned garlic for two decades, and who manages the Orleans Farmers’ Market.

Halcyon Farm is founded on a commitment to use organic methods, but Dinwiddie firmly believes that he won’t ever become a “certified” organic grower, an ongoing process with the additional work of inspections and record keeping. “It’s a personal choice, and for me, I don’t see the benefit for my particular business model. For 99 percent of what I sell, I transfer it directly to the consumer, and there’s no middle man involved.”

Dinwiddie notes that with certification fees calculated on a sliding scale, the extra cost is not a huge factor for him opting out. “Basically I don’t want to pay someone to tell my customers something I can explain to them myself. I don’t need a third-party certification. If you have a following and people trust you, it’s unnecessary.”

“The last thing people should have to worry about is if your food is harming you, but I also worry about that word ‘organic’. It has a certain power behind it.

Like the word ‘democracy’,” continues Dinwiddie. “When you look behind the curtain, there’s a lot to be found there, and is it better or worse? The term “organic” is a huge moneymaker, and it’s a definition that is ever expanding.”

He talks about “the inherent dangers of using and ingesting even naturally-derived substances approved for organic production… substances like pyrethrin, nicotine, spinosad, copper, etc. I don’t want these substances on the food I eat or sell.”

It amuses Dinwiddie that someone watching him foliar feed his vegetables shows concern about the spray until he explains that it’s fish emulsion. A grinning Dinwiddie adds, “Just a personal conviction. We can only really control the things we do ourselves.”

To that end, Dinwiddie believes that consumers know where their food comes from and know to ask the right questions. He will return for his third, nearly 30-week season at the Orleans Farmers’ Market, maybe try the Wellfleet Market, run a small-scale CSA, christen his roadside stand, and sell directly to several restaurants.

Down the line? Devoting more energy to his marketing, and creating a logo and a website. New product offerings like a variety pack of veggies. Year-round growing? Not one to say never, he has sown greens for family and friends in his hoop house. “Fresh mesclun, kale, chard and sweet spinach picked during a Cape winter,” he says, “is just amazing.”

“My vision,” says Dinwiddie, “is not done, but its near 75 percent. I hope to take it to a place where I could hand it over to someone who could steward it onward. Whether I’ll stay here farming this Cape land forever is not a given, but for now, I love jumping out of bed and looking out at the farm. I’m pumped.”

Freelance writer Michelle Koch welcomes spring by planting snap peas and scanning the Atlantic for Right Whales. She works with eighth grade students at Nauset Middle Schooland lives with her daughters Camille and Chloe, and their dog Woof.