Serving Up Hope

A Snapshot of Resourcefulness

Every winter, storms sweep through the Cape, leaving subtly, and not so subtly, altered landscapes in their wake. Over the past year a natural force of an entirely different sort has been with us, not only transforming daily life in previously unimaginable ways but wreaking havoc on the hospitality industry that is so integral to the Cape’s survival. It is too soon to know Covid-19’s ultimate toll. But the alterations on the restaurant landscape are clearly apparent. Not all of them are subtle. Nor are they all bad.

Zoom cooking classes, outdoor winter markets, food trucks, PVC igloos, meal kits and takeout have been life savers for Cape Cod restaurants and the businesses that support them. From the state-ordered closures in March 2020 until now, restaurant owners have repeatedly adapted and tweaked their services to be able to stay afloat while keeping their employees and customers safe. Many that normally remain open year-round have found creative ways to do so at a time when a lot of diners have been reluctant to eat inside. Seasonal businesses have found new ways to keep in touch with regular customers. And farmers and shellfishermen continued to sell their products through the winter, the latter struggling to make up for serious financial losses in the previous season.

Angela Raynor, who owns The Pearl and Boardinghouse restaurants on Nantucket with her husband, Seth, is the Cape and Islands representative of Massachusetts Restaurants United, an organization formed in spring 2020 to secure support for independent restaurants during the pandemic. “We’re all learning together,” she says. Anticipating that her restaurants will serve diners outdoors only this season, Raynor says the Covid experience has forced restaurateurs to consider where the opportunities are to evolve their business models and to make changes they could never have made before.

Chef Michael Ceraldi has continued to hold the weekly Zoom cooking classes that he launched at the beginning of the pandemic. Every Friday from 5-7pm the owner of Ceraldi in Wellfleet Zooms live to participants from the professional kitchen in his Brewster home. A core group of 10-12 people attend every class, though there are frequently more participants. Students routinely check in from London, Norway and California. One week a distant relative from Italy, whom Ceraldi had never met, joined in after seeing the posting on Facebook. “It’s been super cool,” the chef marvels. “I’ve taught cooking classes for 15 years. To me, it’s rewarding beyond getting paid to teach someone how to cook something…learning how to cook with confidence versus just following a recipe.”

Unlike televised cooking shows, Zoom classes allow for two-way communication between the students and instructor. Corianna Yannone, who works at Ceraldi, facilitates the technological end, passing along questions participants type in during instruction. And participants can hold their work up to their computer’s camera for feedback. “If someone’s malfatti isn’t looking right we can troubleshoot live,” Ceraldi says. “It’s an awesome format.”

In his restaurant, Ceraldi relies almost exclusively on Cape Cod-grown ingredients, highlighting the farmers, fishermen and others who grow and produce them. This year he has extended the focus on these same purveyors to his classes, building a session, say, around mushrooms and inviting Uli Winslow of Cape Coastal Farm Products in Truro as a guest speaker. “My whole outlook is to promote independent business owners on Cape Cod and my community,” he says. “That’s what Jesse [Ceraldi, his wife] and I are passionate about – making food from people we know.” Ceraldi is hopeful that the restaurant will be active during the summer season. But no matter what happens, the Zoom classes are here to stay.

In Falmouth, Osteria la Civetta owner Sara Toselli explored replacing the restaurant’s in-person cooking classes with Zoom classes, but ultimately shifted to Covid-safe private classes after the initial lockdown period eased. Toselli, who like the rest of her staff is from northern Italy, says, “We were seeing what was happening at home and talking about what we were going to do should what was happening in Italy happen here. When it did happen, it maybe wasn’t as surprising for us as it was for other businesses.”

Her restaurant began offering takeout on March 16, 2020, the day after restaurants were forced to close. “For takeout, we thought we could give customers the option to make their own meals at home,” she says. Osteria la Civetta now sells grocery items including some of its own sauces and homemade pastas, as well as oils and cheeses, in addition to fully prepared dishes. “We try to give exactly the same ingredients we use in more of a home setting,” Toselli says. “We needed a little bit of adjustment because that wasn’t part of our business model.” But the move has paid off.

Throughout the pandemic Toselli has been able to employ her entire staff, which has been particularly important because none are American citizens, therefore not eligible for unemployment compensation. These days, Osteria la Civetta has what its owner calls a “more unapologetic approach to the menu.” By necessity, it is smaller than before, “and when we run out we run out.” Regardless of what the Covid situation is in the coming season, the restaurant will continue to offer cooking classes, takeout food and groceries. “We learned so many more ways to engage with our customers,” says the restaurateur. “Those are changes that will stick after Covid.” But she will likely scale back from being open six or seven days a week to five, explaining, “This was a wake-up call. We were working ourselves to a degree that was not feasible. We have to work in a way that is healthy.”

Working up to or past the point of exhaustion is practically part of the job description in the restaurant business. And the pandemic has only heightened the pressures. Last summer travel restrictions kept the usual pool of seasonal employees from the Cape, so owners and managers struggled with dramatically reduced staffs. In mid-winter this year, many expressed ongoing concern about filling positions. Notes Raynor, “Because so many people are leaving the cities, the housing situation will be a challenge for people who are going to want to come work for the season.”

Trudy Vermehren, owner of three-year-old Fox & Crow Cafe in Wellfleet, had just had heat installed in the dining room in December 2019 and was excited about being open year-round. Just over two months later, she had to close for several weeks, reopening in mid-April with outdoor seating only. By the summer, Vermehren had to scale back the full dinner menu and bar service she had planned because she could not fill nighttime staffing. Still, she says, “I feel like we’re lucky in many regards because we’re really small. We can shrink and expand the menu. We can adapt and change options constantly in response to the season and available staffing.”

Vermehren’s community was also lucky. In March 2020, at the suggestion of her attorney and with his contribution to get things started, Fox & Crow launched Common Table, initially to provide breakfasts for some of the children who would not be receiving them when schools shut suddenly. Vermehren posted the initiative on Facebook, raising $11,000 in 24 hours, an amount that eventually more than tripled. The program ended in mid-March of this year, after serving more than 20,000 meals. “It’s been a really good experience to have this happening as the restaurant is operating because it’s kept us very aware of how to stay safe,” she maintains.

As of late February Vermehren still did not have summer staff lined up. “There’s no housing. I’m really struggling,” she says. But she continues to focus on her goal of being open at night. “I have a certain menu I want to implement. I’m really focused on keeping the business viable and open for people.”

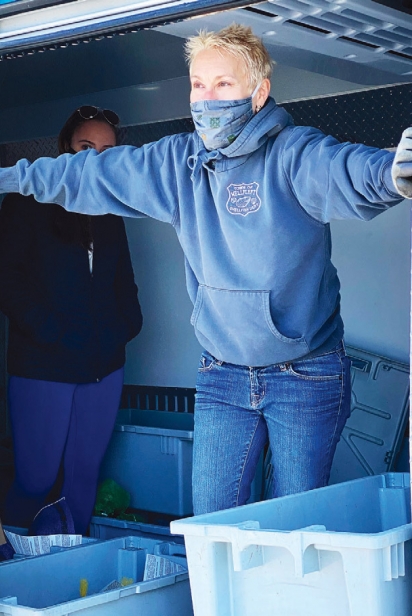

Down the road from Fox & Crow, the Wellfleet Shellfishermen’s Farmers’ Market has been selling out every Saturday since December 12. After widespread Covid-related restaurant closures wiped out at least 50 percent of their business, Wellfleet shellfishermen (the term includes women, who prefer the term) were facing a bleak winter. In the fall the Wellfleet Shellfishermen’s Association board, with advisors including shellfish constable Nancy Civetta, came up with the idea for the market. Because Massachusetts does not allow direct-to-consumer shellfish sales, Wellfleet-based Holbrook Oyster agreed to act as the dealer, taking only a small percentage of sales, leaving significantly higher profit for the shellfishermen than is standard.

“All the guys tell me what a huge difference it makes in their life,” says Ginny Parker, Wellfleet Shellfishermen’s Association president. “It’s real money. Particularly for wild harvesters, it’s a big opportunity for them that they wouldn’t have had.” It is also an opportunity for oyster lovers to get to know the people who grew and handled their oysters. Repeat customers who buy from different growers can learn about the diversity and flavor nuances of oysters from different areas within Wellfleet Harbor. The market is set to end in early May but Parker promises that online sales will continue.

The Orleans Farmers’ Market, which has operated year-round for the past six years, spent its first winter outdoors in 2021. In past years, the winter market was held in the cafeteria of the Nauset Middle School. But, market planners didn’t know whether they would have access to the building this year if school was closed due to Covid. Board of Directors president Gretel Norgeot also adds, “Vendors had product and they had customers who wanted them to be there.” Even when the weather turned from mild to messy, “We decided to just keep going,” she says. “Turnout was awesome.”

Every Saturday from 11-1 the winter market had seven vendors, selling fresh eggs, mushrooms, lettuce, honey, locally-raised beef and chicken, baked goods, prepared foods and alpaca yarn. With support from the Massachusetts Farmers Markets’ Winter Farmers Market Initiative, Orleans market workers erected two MarketSheds in late February. As intended by the Initiative, this ensured that residents would be able to continue to have the benefits of the farmers market during the winter while limiting exposure to Covid.

The three PVC igloos outside of Jake Rooney’s Family Restaurant in Harwich Port may not be there by the time you’re reading this, but according to general manager Kate Lomask, they were so popular that the Covid-inspired innovation may become a permanent off-season feature. Lomask was in Provincetown last August with her father, Jake Rooney’s owner Peter Klaus, and saw igloos outside Liz’s Cafe. The pair thought they were a great idea and ordered them for their restaurant, which has always been open year-round.

“They’ve been packed,” Lomask says of the cozy units, which can accommodate six people. With two space heaters each, and built on platforms instead of directly on the ground, she maintains they are comfortable even on the coldest days. “Some other restaurants have them, but we understand ours are the warmest,” she says. When we spoke in early March she was planning to keep the domes up until the weather got warm, then offer outdoor tented seating, depending on what the town allowed. The igloos helped business so much that even through the winter the restaurant was operating almost at summer staff capacity.

Pizza is a staple to-go option, so shifting from full-service to take-out should have been relatively easy for Pizza Barbone in Hyannis when the pandemic hit. But chef-owner Jason O’Toole explains, “If your restaurant isn’t set up for [take-out], it’s a huge change.” Shifting from roughly 10% to 100% take-out involved completely reconfiguring the dining room. Instead of accommodating diners, tables held pizzas ready for pickup; banquettes were piled high with pizza boxes. O’Toole explains that the wood-fired Neapolitan-style pizza his restaurant is known for is much better eaten in-house, but feels lucky that people still love his pizza and are buying it. And, he notes, “We haven’t laid off anybody.”

The restaurant, which began as a mobile pizza oven, still maintains food trucks, usually for private catering. Over the winter, those trucks headed to Truro for Saturday and Sunday pop-ups on the lawn at Truro Vineyards. There, O’Toole says they sold a few hundred pizzas every weekend.

The chef anticipates a “crazy” 2021 season. He hopes to have more outdoor seating than he did last summer. Like many, he is concerned – actually, he’s “freaking out” – about staffing, largely because there is no available housing. He just hired four young workers from Kazakhstan. “I have no idea what their skill set is. They can at least dish wash and I’ll train them to stretch pizza dough,” he says.

What the coming season will bring is still an open question, but with vaccines and a year’s worth of experience, the altered landscape includes optimism.

boardinghousenantucket.com

ceraldicapecod.com

osterialacivetta.com

thefoxandcrowcafe.com

wellfleetshellfishermen.org/collections/buy-shellfish-online-wellfleet-oysters-quahogs-littleneck-clams-and-scallops