Amy Littlefield Handy

Born a year before the Civil War, married at 30, widowed at 47 and left with two teenage boys and her husband’s family’s rambling house and farm on Cape Cod, she led a long and productive life. Her name was Amy Littlefield Handy: single mother, farmer, keeper of bees and turkeys, author, artist and patriot. Several generations of our family have grown up in her shadow, in the Barnstable house that she built, enriched by her drawings and family things, including an antique map chest filled with blue-backed coastal maps of Argentina, Columbia and the Windward Passage dating from the 1830s, as well as a roll of posters produced by the Food Administration during the First World War.

Early Years

She was born in 1860 in Milton, Massachusetts, where she learned to love the woods and flowers, inspired by her 90-year-old grandfather Samuel Littlefield, a farmer, and her Aunt Lydia, a gardener. There were flowers and strawberries in spring; black, white and red raspberries in summer; hickory nuts, chestnuts, grapes and apples in the fall. One tree in their orchard bore two different kinds of apple, which her grandfather explained was the result of grafting. Writing later in life, on the Cape, she remembered it all vividly:

I can bring back all the odors of that garden right here and now on a cold autumn day by just closing my eyes and feeling grandpa’s hand holding mine…odors of the little ladies delights under our feet and the grape blossoms overhead on the arbor. I think that right then and there I learned to love a garden.

She also learned to love vegetables:

I knew as soon as the carrots and turnips were big enough to pull and I pulled them, wiped them off on the grass and ate them freely. I fancy in those days, raw vegetables were considered uneatable, and if my habit had been discovered, I should have been forbidden to keep it up, but as it was not, I feasted when ever I felt inclined.

After finishing high school, Amy took art classes at the Museum School in Boston, and in 1890, she married Edward Adino Handy, a Barnstable native who had graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. His education was financed by his schoolteacher sisters. By the early 1900s Mr. Handy was General Manager of the Lakeshore and Michigan Southern Railroad. His family, which now included sons Jack and Ned, spent winters in Ohio and summers in Barnstable where Mrs. Handy tended cows, chickens, and a very productive vegetable garden. Gardening clearly had become a passion; at the 1905 Barnstable County Fair (then just east of the old Bacon Farm on Route 6A), the boys earned a prize in the children’s department for vegetables—46 different varieties—and were awarded $3. Amy had started the category two years earlier, according to the local paper. Four years later, she would win a first prize ($5) for her essay on growing asparagus.

In 1907, Edward died, and Amy moved to the family farm in Barnstable, becoming a full-time Cape Codder. Cooking went hand-in-hand with all of the farm’s produce, and in 1911 the sales table at the Fair featured a small cookbook that she had compiled and illustrated, called What We Cook on Cape Cod. Joseph Lincoln wrote the forward, a poem, reproduced in part here:

A Cape Cod cook book! You who stray

Far from the old sand-bordered Bay,

The cranberry bogs, the tossing pines,

The wind-swept beaches’ frothing lines,

You city dwellers, who, like me,

Were children, playing by the sea,

Whose fathers manned the vanished ships –

Hark! Do I hear you smack your lips?

A Cape Cod cook book My, oh my!

I know that twinkle in your eye…

I know that smile of yours; it tells

Of chowder, luscious as it smells…

A Cape Cod cook book! Why, I’ll bet

The doughnut crock would tempt you yet!

A Cape Cod cook book! Here they are!

A breath from every cookie jar…

Thanksgiving, clambake, picnic grove,

Each lends a taste, a treasure trove;

And here they are for you to buy –

What’s that? You’ve bought one? So have I.

1913 was a banner year. Mrs. Handy won first prize as a farmer (as opposed to a professional grower) for her collection of vegetables and for potatoes and onions as well. Son Jack won a blue ribbon for his Jersey cow. Other prizes went to her Delap Hill Farm for Orpington chickens, guinea fowl, Toulouse geese, Bronze turkeys, and Indian Runner ducks. The grand total was $39.

Although England declared war on Germany in 1914, life on the Cape continued much as it had. In January, Amy went to the Poultry Show in Boston, where her fowl took a number of prizes. She won four blue ribbons at the County Fair that summer, for livestock and poultry. Writing also took much of her time; What We Cook on Cape Cod was published in 1916 by the Shawme Press in Sandwich, and is a prized collectible today.

Meanwhile, Amy designed and supervised construction of a smaller house on the family land, insisting that it “…be a Cape Cod house and when it is finished it must look as if it had been here a hundred years!” It was her own adaptation, with spacious light-flooded rooms. She painted a harbor scene on a bathroom wall that is still a family favorite. With minimal changes, the house has served four generations well.

The War Years

Americans increasingly had their eyes on Europe, and their minds on food. German U-boats were destroying shipments of food in the Atlantic Ocean, and in April England reportedly had only enough wheat to last for six weeks. Herbert Hoover, as head of America’s Relief Administration, was successful in getting quantities of food to Europe to forestall starvation. Then in August, President Wilson established the Council of National Defense as a civilian preparedness commission, whose goal was to support the war effort by protecting the country and its resources—including food—and by boosting public morale.

Late in 1916, Wilson was elected for a second term, having run on the slogan “He kept us out of war.” Then Germany announced unrestricted submarine warfare, sank several American ships and tried to entice Mexico to enter the war, promising U.S. territory as the reward. Wilson’s term began in March 1917 and war was declared against Germany a month later.

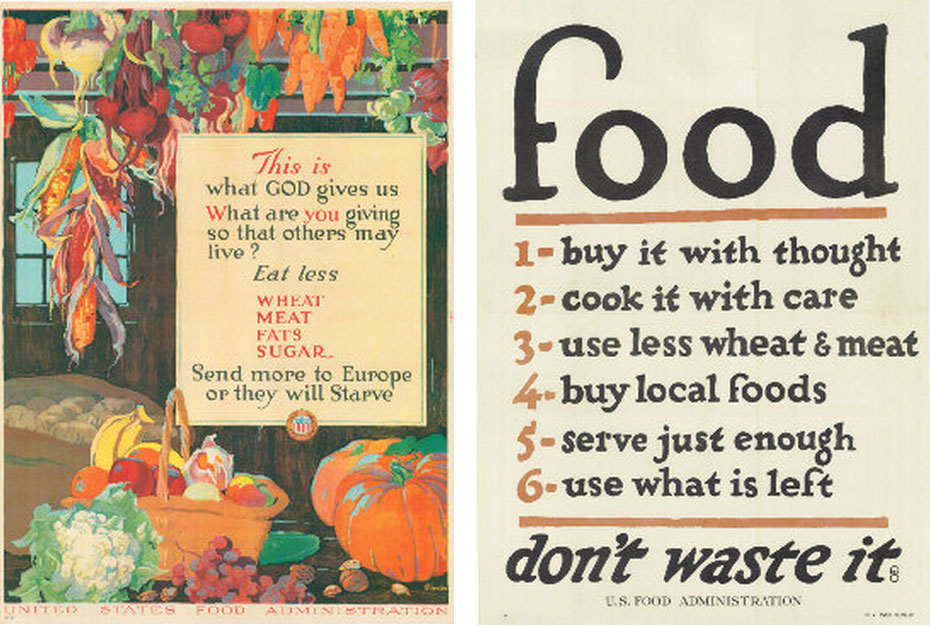

Saving food became a common cause. Hoover was appointed head of the United States Food Administration, convinced that food would play a major role in winning the war. Loyal citizens were asked to conserve food in a campaign supported by community programs, slogans, and posters. All efforts were to be voluntary: Hoover served without pay; the Wilsons grazed sheep on the White House lawn; over 20 million Americans signed the Administration’s pledge to conserve food; and more than three hundred artists volunteered to help design the campaign’s posters, which were being created in profusion.

In May, states were encouraged to set up local Councils of Defense. Some states, including Massachusetts, created Women’s Committees of National Defense as well. The surge of patriotism reached Barnstable, and by the third week of May, Amy had penned an article in the The Hyannis Patriot, “To the Women of Cape Cod,” calling for local women to exercise their patriotism by participating fully in the war effort:

A great impetus has been given to plowing and planting throughout the United States. Our Cape is showing the results. To be of real use it must be followed by careful gathering and distribution which rests largely with the men, but equally important is utilization and economy which is our work.

She went on to describe the great responsibility that housewives have for the effective “utilization of all our garden products” and the efficient “economy of all food stuffs”.

By July Mrs. Handy had been appointed Chair of the Women’s Committee for the Council of National Defense, Town Unit, including Barnstable and West Barnstable. Food conservation was clearly on her mind, and she wrote an article about it in The Hyannis Patriot on the 30th, with three recipes included. That same month, her second book, War Food, was published by Houghton Mifflin, and addressed the challenges brought on by wartime shortages. Conserving wheat had become a national priority: wheat products lasted, and the country’s stores were needed for supplying the troops. In American kitchens, recipes were being invented and adapted using ingredients like potatoes, rye flour, and cornmeal. In the course of her efforts to help conserve food, Amy recognized the historic and artistic merit of the Food Administration’s colorful posters, and managed to conserve some of them as well.

The Public Market

In August, she wrote an article announcing that, “Barnstable is to have the first Public Market established on the Cape,” to be held every Saturday at the County Fairground. This was a joint project of the Men’s and Women’s Committees, and an ingenious idea, with a strong emphasis on efficiency and locally grown food. Although these ideas are familiar to us today, the concept that Amy was instrumental in developing was quite different in spirit from the farmers’ markets that we know now.

To this market everyone having surplus vegetables, chickens, fish, berries, or any other food stuffs is free to bring his products and offer them for sale. There is no doubt that summer residents and others who have no gardens will gladly seize this opportunity to obtain fresh vegetables in place of the goods brought down from Boston which are now being offered in the shops. It is of vital importance for the welfare of the country that nothing that has been raised this year shall be wasted and that nothing shall be transported by the already over-worked railroads which can be avoided.

Amy played an active role in the Food Administration’s efforts. She wrote in The Hyannis Patriot again that month, encouraging gardeners to take advantage of the Public Market. “In this way there will be no food stuff wasted and those who have planted more than usual at the instigation of the government will get their money back.” She explained that the market was established following the instructions of the government, and reported the opening day as having been very satisfactory. “There were all kinds of fresh vegetables for sale as well as apples, berries, eggs, pickles, preserves and cottage cheese. The buyers came early and everything that was brought in the morning was sold.” She added that as Saturday tended to be such a busy day in the home, much of the selling was done by children—and done well at that.

Through the winter of 1918 Amy was busy with committees and writing. March saw the publication of War-Time Breads and Cakes, again by Houghton Mifflin, in which she addressed the dire need to conserve wheat and sugar. She was a member of the Massachusetts Food Conservation Board, and actively gave her services to schools and women’s alliances with demonstrations and talks about war foods. Efforts to preserve, can, and dry fruits and vegetables were also encouraged, and she lectured and wrote about them all.

In June of 1918 The Hyannis Patriot reported that Mrs. Handy had recently “addressed every high school in the county…, enlisting the girls in some sort of farm work for the summer.” The Women’s Land Army had been established in 1917, modeled on a British program. The goal was to provide farm labor to replace the men who had gone off to war, and ultimately the program employed 15,000-20,000 women, mostly college educated and from urban settings. In addition to the Land Army, the government sponsored the U.S. School Garden Army, and this probably was the program that Amy was involved with in the spring of 1918. There was also a National War Garden Commission that encouraged victory gardens and home gardening in general. The posters that were created about these programs are also appealing, although Amy didn’t include any in her map-chest collection.

In August The Hyannis Patriot declared the community market a successful undertaking, thanks largely to Mrs. Amy L. Handy of Barnstable. The previous week’s market had disposed of sixty dollars worth of commodities, including seven dollars worth of clams. With the wheatless Mondays, meatless Tuesdays and porkless Saturdays encouraged by Mr. Hoover, local seafood had become an increasingly important source of sustenance and protein.

Final Chapter

November of 1918 brought the Armistice. Amy was almost 60 years old, and no doubt her vigor for gardening was waning. She remained an active member of the Barnstable community, collecting produce, jams and jellies for a Christmas basket for a local church and hosting parties for the Civics Committee. She also found time to reminisce about her childhood, recording pages of memories of Massachusetts life in the period just after the Civil War. She enjoyed picnicking in the dunes with her grandchildren, although she worried about what her grandmother would have thought. She had been raised in an era when legs were never to be mentioned in polite society (the proper description apparently was “lower limbs”), and in her mother’s household, women were to behave in a manner that exemplified dignity. Sand dunes and sandwiches might not have met those high standards.

Amy died in 1941, but her legacy remains. Copies of her cookbooks are included in the collection at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library, her drawings and watercolors treasured by her progeny. And today, her turkey house is the base of operations for our vegetable garden.

Susan S.H. Littlefield grew up during summers at her grandmother’s house in Barnstable. After graduating from Harvard, she worked with the garden editor at House & Garden magazine and got a degree in landscape design. She is the author of several garden books, including Visions of Paradise. She has lived in Florida, California and Argentina, and currently lives in New York City; but she, her husband, and their three children all consider Cummaquid their home base. She enjoys cooking, gardening, writing and painting with watercolors – much as her great-grandmother did.

Edward Otis Handy, Jr. (“Ned”) is Susan Littlefield’s father. He grew up in Barnstable; graduated from Harvard and Harvard Law; served as a Marine officer in Korea; worked in Providence for Textron Inc. and in 1991 retired and moved back to his childhood home. He has since written two small books about Barnstable. He, his wife Sue, his children and grandchildren all have a love for gardening and Barnstable.