Turning Sand to Soil: Eastham's New England BioChar

What if there was something that could take all the agricultural waste here on the Cape, from tree trunks to brush and, crazy as it sounds, cleanly and efficiently turn it into something that would make the Cape’s sandy soil fertile? And what if this process also made plants stronger, healthier, and therefore, better tasting? What if, then, you could feed it not just to plants, but to animals, and it would have the same effect. Chickens and cows would be healthier (and therefore, better tasting).

This supposed silver bullet is biochar, and it may or may not be too good to be true. On Cape Cod, biochar is being manufactured by Bob Wells and the company he founded in 2009, New England BioChar, on a six-acre farm in Eastham, back in the woods abutting the National Seashore. Wells makes a pretty good case for it being true, but he doesn’t expect you to take his word for it. He’s done his homework, and he insists others do theirs, too. Wells was raised by two journalist parents, but he hadn’t heard the journalist’s adage, If your mother says she loves you, get two more sources. “I like that,” he said, clearly tickled. “I’m going to keep it.”

Biochar is a soil additive that must be at least 60 percent carbon made from a process known as pyrolysis, the heating of organic material in the limited presence of oxygen. Fire requires fuel, heat, and oxygen. But since pyrolysis doesn’t use oxygen, Wells has devised a way to make biochar that is 90 percent carbon while also dramatically reducing the amount of toxins released into the atmosphere, by using toxic gases released from the heated wood to further break down the wood into biochar.

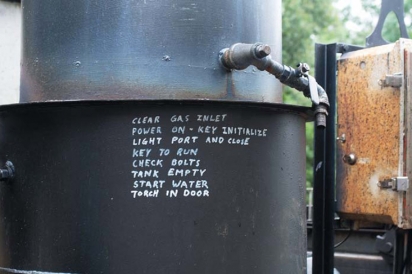

In Wells’ process, split wood is piled into a double-walled, airtight container called a retort. The initial heat used in his process is achieved by setting fire to wood chips in a combustion chamber. The heat generated from the burning wood chips is circulated between the double walls and surrounds the wood. As the wood is heated to temperatures as high as 1000 degrees Fahrenheit, the wood begins to smoke. At this point, no more outside heat is needed for the self-contained retort. Rather than going up a chimney, the smoke filled with toxic gases is cycled back through a condenser where all the toxins are reduced from the smoke except for carbon monoxide, hydrogen, and methane, which all happen to be excellent fuel sources. Wells’ environmentally friendly method then burns those three gases to further heat the wood, keeping the gases from exiting into the atmosphere, leaving virtually nothing left of the original biomass but the carbon left in the wood at the end of the process.

New England BioChar appears to be the culmination of all of Wells’ life experiences. He doesn’t have a college degree. He practices a life-long exercise in self-education as a hands-on learner that has given him an incredibly broad scope of knowledge spanning many topics. He can converse with ease on topics as complex and wide-ranging as engineering, physics, chemistry, biology, or botany; you can pretty much name it and he can talk about it. “I don’t fit into academia,” he says very matter-of-factly, the way he explains just about everything, in a quiet, organized way that reflects his thinking. “I wanted to learn what I wanted to learn, not what they wanted to teach me. I love to study and research. Once I feel I’ve mastered a subject, I lose interest,” he said. All his life Wells has basically just followed his nose, a practice that ultimately led him to learn about biochar.

In 2004 he and his wife, Connie, moved to their house in Eastham that had been in her family since 1967. A parcel of land abutting their property was put on the market – six acres of overgrown land with no road access. The Wells’ offer was accepted, and Wells quit his job managing a business and threw himself into the task of single-handedly clearing the land with the idea of growing organic vegetables. “It didn’t take me long to realize the soil I was working with was terrible. It was just sand,” he said. “I was too stubborn to give up. I looked into ways to amend the soil, and I started hauling in organic matter and making compost.”

In the meantime, Wells read the book, 1491, a history of the Americas before the Europeans arrived. “There were a few paragraphs that caught my attention about a soil that was so rich and fertile, that after being abandoned after 500 years it’s still an order of magnitude more fertile than any other around it,” he said. This soil is terra preta, Portuguese for “black soil”, a soil found in the Amazon basin, a combination of organic material and charcoal. “Biochar is a modern version of terra preta,” Wells said.

“When I started playing with biochar, it blew me away how different the crops were,” Wells said. “My first foray was making a little bit and using it on turnips, and it made such a difference that the turnips looked like a different species. I made some charcoal, ground it up, put in the soil and planted maybe a fifty-foot row, and they were twice as big as the others.”

The word biochar has evolved from an earlier one, agrichar, to distinguish it from the everyday charcoal fuel used at cookouts. Biochar is a soil additive, not a nutrient. Organic matter still needs to be added periodically to soil while biochar, once applied, will remain for thousands of years. Proponents of biochar say it makes soil more fertile by improving water and nutrient retention in turn increasing microbial activity and water storage. Healthy, sustainable soil comes from a thriving microbial community, and proponents say that biochar gives nutrients and microbes a medium in which to thrive.

Wells compares biochar to high-rise apartment buildings sheltering a population of billions of microbes. Just like tiny Rhode Island’s undulating coastline measures 400 miles long, or the folds and grooves of the human brain dramatically increase its surface area, the surface area of a piece of biochar small enough to fit on a teaspoon is enormous because it is riddled with millions of chambers in which microbes can thrive and grow, and nutrients persist.

Wells began making biochar on a small scale in 2008, modifying the plans for a retort from Chris Adams, whose LinkedIn site identifies him as an industrial designer, appropriate technologiste, and renewable energy consultant in Ethiopia. “It was made of masonry and was a very basic retort,” said Wells.

Wells immediately converted Adams’ plans from its stonework structure to steel because he was a welder and was more comfortable working with steel. Steel also allows Wells’ design to be moved to wherever a biomass is located. Wells didn’t stop there with the modifications. With Adams’ design, heat escapes that Wells realized could be recycled and reused in the process, and while Adams’ retort eliminated 75 percent of the smoke released into the atmosphere, Wells was determined to eliminate the other 25 percent. “It’s never final,” Wells said about modifications. “It’s a long evolution.”

Wells’ current modified Adams’ retort is 20 feet long with a 17-foot-high chimney, its dimensions allowing it to fit comfortably in a shipping container for delivery to customers. Almost entirely hand-made, it is a thing of steampunk industrial beauty with shaped flat-black-colored steel, each component unfolding upon one another with a laptop connected for precise monitoring of the operation.

Designed by Wells on a computer-aided design system that he, of course, taught himself, the parts are fabricated from Wells’ plans on a computer-aided manufacturing system in a shop run by Ryan Sverid, New England BioChar’s production foreman. Sverid was born in Wellfleet but now lives in Eastham. He, like Wells, has worked numerous jobs from construction to marine work. When they met, he was working for a paving company. “I’ve worked at a lot of different places,” Sverid said. “What I do at New England BioChar is the collective knowledge of everywhere I’ve worked. I’ve had to work on engines that couldn’t fail. If you can work on a boat or on a house, you can do this work,” he said.

In this time of information overload and disinformation, it’s always good, as Wells notes, to get two more sources. Biochar currently is not approved by the FDA for use in livestock and chickens, but a quick Google search shows that it is approved for that use in Europe, and that there are farmers and food producers in the United States using it for that reason. Used in a chicken coop, the theory goes, charcoal absorbs the ammonia generated by chick manure that, in turn, is lethal to chicks and their tiny, newly developed lungs. But when chicks ingest the biochar that has absorbed the ammonia, it is passed along through their digestive system into their manure that can be put safely in the earth where it feeds microbes. Also, in a simplified version, the same theory applies to livestock, with biochar absorbing the methane that is produced in one of cattle’s four stomachs and is stored and expelled in the cows’ manure.

Scientists, those individuals who require even more than two sources, continue to investigate the merits of biochar, chiefly questioning if a substance that lasts for thousands of years should be put in the soil. The Amazon’s terra preta seems to answer that question. There is also a question about polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH), carcinogens that can be produced during biochar’s manufacture. Wells’s response is that his biochar has an insignificant amount of PAHs because it isn’t made at temperatures high enough to produce PAHs.

But if the jury is still out on biochar, Wells isn’t waiting; he continues full speed ahead. Wells has gained sort of celebrity status in the biochar community, and he says he receives hundreds of emails daily from people from around the world with questions about biochar. “The shorter list would be which countries I don’t hear from,” he said. He has conducted demonstrations, classes, and workshops along the West Coast and up and down the East Coast of the United States, and in China and Canada for universities, garden clubs, organic farmers, farm bureaus, high schools, and other educational organizations. He presented at the International Biochar Initiative conference in Rio de Janeiro in 2010 and continues to present at other conferences.

On Cape Cod, New England BioChar uses wood waste from landscapers and tree surgeons that is cut up and split for the biomass. “In my part of Cape Cod, it costs $200 a ton to haul it off Cape, so biochar is a way to economically rid the Cape of waste,” said Wells. He also uses fish waste in compost, again saving fishermen the expense of disposal.

New England BioChar sells its product with and without organic material added. His mixed biochar is a combination of 60 percent biochar and 40 percent compost that Wells makes himself, adding earthworm castings and what he refers to as a “secret sauce” composed of what he says are beneficial microbes and fungi. It can be found through ecologically minded landscapers who use it in their work, and at Ace Hardware in Eastham and Hyannis Country Garden. His biggest customers are municipalities, including the town of Orleans and the City of Cambridge, and large landscaping companies. “Pot growers also appreciate it,” Wells said.

He has built and shipped his retorts, which can take up to a year to fabricate, for customers in Chile, Indonesia, twice in China, and throughout the United States to customers in California, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, Texas, Arizona, North Carolina, South Carolina, Florida, Michigan, Vermont, New York, and New Hampshire. “Lots in New Hampshire,” he said.

Particularly in light of today’s news where there is a car named after Nicola Tesla, when you’re in the presence of Wells you can’t help but draw comparisons. Wells is such a rare human being, self-educated to an extraordinary level, motivated, and accomplished. You hate to wonder if 75 years from now only the cool people will know his name and what he’s known for, his achievements appropriated by some billionaire type. Whatever the next step is for biochar, acceptance or rejection, Wells deserves watching. Whatever he does, it will be worth watching.

John Greiner-Ferris is a freelance writer and photographer.

New England BioChar

newenglandbiochar.com