Salty Air

“Salt is born of the purest of parents: the sun and the sea.” -Pythagoras

In West Brewster where Airline Road and Old King’s Highway meet, sits a small cemetery, domicile to only 124 headstones. On one nondescript grave, veiled by green moss and sinking into the earth, is engraved the epitaph “John Sears, Inventor of the Salt Works, Aged 72 yrs.” If you weren’t searching for it, Sears’ grave would be easy to overlook. Curiously the industry he helped pioneer has suffered a similar fate. Few people today realize that for generations of Cape Codders, salt was the region’s lifeblood, its ‘white gold.’ Today salt is ubiquitous and cheap, an ingredient for casual regard. Yet its history on this strip of land weaves a tale of good old-fashioned Yankee ingenuity, a story that earns salt a place among the ranks of the Cape’s more illustrious locals, cranberries, clams and cod.

To appreciate the historical importance of salt it is useful to consider America’s current relationship with oil. Driving our transportation and food production systems, petroleum is of incredible strategic importance to the American economy. Before refrigeration, salt occupied a comparably strategic niche as an agent of food preservation. New England’s mighty fishing industry was heavily dependent on salt. Salting cod transformed a good that would otherwise spoil quickly into a lucrative commodity that could be traded overseas. Additionally, salted food provided sailors with a durable food source, permitting longer stays at sea to turn greater profits. Fathoming life without salt would have been near impossible, so integral it was to the fabric of everyday life. However, as with oil today, the colonists relied heavily on the importation of foreign salt to meet the high demands of the fishing industry.

Britain was the primary purveyor of salt to the colonies. As the American Revolution gained momentum, this dependence on Britain became more and more of a liability. Intimidated by America’s flourishing trade and fearful of losing its colonies, Britain began heavily taxing salt exports and even physically blockading American salt reserves. Salt became scarce and imports sporadic. Responding to British aggressions and motivated by the prospect of political and economic independence, in May of 1776 the Continental Congress issued a bounty on salt. For every bushel produced at home, equal to eight gallons, Congress would reward one-third dollar. The incentive had its desired effect, spurring the construction of saltworks all along the Eastern seaboard. At that time there were no known rock salt mines in the colonies, as there were in Europe. One opportunistic Yankee from Dennis, John Sears, had already been mulling over the idea of harvesting salt by solar evaporation when Congress’ bounty came along.

The following summer John Sears constructed Cape Cod’s first salt works in Sesuit Harbor. After building a wide, shallow, wooden vat to collect salt as seawater evaporated, Sears spent his summer laboriously hauling water into the vat, one bucket at a time. Sears’ neighbors mocked him; they regarded his pet project as a futile pipe dream. Indeed, Sears probably looked rather silly lugging buckets of water into a leaky, wooden basin. Further complicating Sears’ efforts, was that the vat often overflowed when it rained, which allowed the sea to reclaim much precious salt. Still, Sears’ labors rewarded eight bushels of salt. Despite the imperfections of Sears’ initial design, solar evaporation proved to be more efficient for harvesting salt than boiling seawater, a method resorted to during times of scarcity. Gleaning salt in this way demanded copious amounts of wood to maintain fires for boiling. Two cords of wood and 400 gallons of seawater would yield only a single bushel.

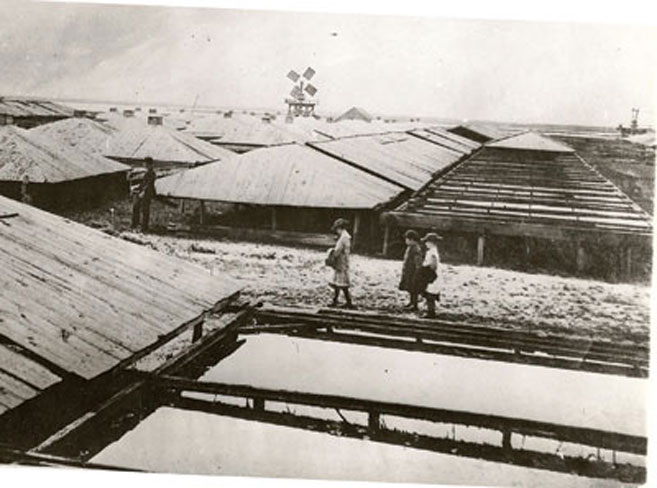

In the ensuing year Sears improved on his design by reinforcing the vats with caulking. He also stumbled on a bit of good luck, literally, while strolling the beach one afternoon. When he found a ship’s abandoned bilge pump on the shore, Sears had the notion to readapt its use. With a windmill generating power, Sears rigged the pump to siphon water from the ocean into his salt vat. This ingenuity eliminated hauling water manually from the sea—Sears’ most arduous and time-consuming work. The second time around, Sears’ saltworks returned 30 bushels. The neighbors quit laughing. Soon thereafter, saltworks became a fixture of Cape Cod’s seaside landscape.

With its miles of open coastline, Cape Cod proved a desirable setting for this growing industry. Despite the limits of New England’s colder climate, the raw materials needed to establish a saltworks were inexpensive and accessible, and provided broad opportunities for wealth. Small investments returned great profits, even after the first year. Rueben Sears (unrelated to John Sears, but also a denizen of Cape Cod) was responsible for a simple innovation that greatly improved the efficiency of John Sears’ design. Rueben devised a sliding wooden cover to shield salt vats from inclement weather. Opened in the morning and covered in the evening, these roofs extended the harvest season beyond the narrow window of summer. The industry was so important to the community’s economic health that townspeople would race to help cover the saltworks when rain threatened. Salt became as integral to Cape Cod’s economy as its abundant fisheries.

The fishing industry and saltworks propelled each other and also boosted complimentary businesses such as shipbuilding and the fur trade, where salt was used to preserve pelts. However, ultimately it was political unrest that maintained such a profitable market for salt. With the suspension of imports during the Revolutionary War, the price of salt skyrocketed from fifty cents to eight dollars a bushel in 1783. After the American Revolution, embargoes continued to prohibit trade between the States and Britain. Fearful of a devastating salt shortage, several states including Massachusetts continued to subsidize the salt industry. These measures stimulated local economies and kept the price of domestic salt low. For half a century from its inception, the saltworks continued to grow and amass wealth in the region. Near the industry’s peak, over two million dollars were invested in Cape Cod’s saltworks.

As saltworks evolved from necessity, so too it waned as necessity lost its urgency. With the shifting tides of industry, Cape Cod’s saltworks began to decline around 1830. A combination of factors influenced the industry’s downturn, including the founding of saltworks along New York State’s salt springs in Onondaga. As oceanfront operations, Cape Cod’s saltworks were vulnerable to enemy attack. This was particularly undesirable since tensions between Britain had not dissolved, even after the turn of the century. The British exploited this weakness during the War of 1812. While British vessels roamed Cape Cod’s waters during the war, Commodore Richard Ragget of the H.M.S. Spencer threatened to destroy Brewster’s saltworks, should the town fail to pay a $4,000 ransom. Fearful for the safety of their saltworks, Brewster complied. Then, Spencer also managed to extort a sum of money from Eastham.

Since the state is geographically isolated, investment in New York’s saltworks was considered a wise expansion, a way to diversify major salt producing regions. With lumber and acreage more abundant than on Cape Cod, New York began outpacing Massachusetts’ coastal saltworks. In 1808 New York lawmakers began to seek funding for a waterway to connect Lake Erie with the Hudson River, a project that would provide an efficient commerce route to New York City. In 1825 the Erie Canal was completed, marking the beginning of the end of Cape Cod’s saltworks. John Sears passed away in 1817—fortunately not living to see the demise of his enterprise. In 1837 the Cape was home to 658 saltworks. The industry declined steadily over the next 50 years and by 1888, the last had closed its doors.

Today there is little evidence of the saltworks’ reign on Cape Cod. Regrettably, the saltworks did leave one legacy—its devastation of the region’s old growth forest. Shipbuilding practices and salt vats consumed vast quantities of wood. This forest depletion made agricultural endeavors even more difficult on the Cape’s sandy soil. White pine, now rare, was once abundant on Cape Cod. Despite the seemingly harmonious and lucrative relationship the fishing industry and saltworks shared, the continued use of natural resources in this way would have ultimately proved unsustainable. Still, Cape Codders were thrifty. As each saltworks went out of business, the salt vats were dismantled to construct houses. The wealth of the era is thus preserved in the stately homes that line our older roads.

Perhaps the growing market for local products will revive Cape Cod’s salt industry. The Maine Sea Salt Company, opened in 1998, uses solar evaporation from spring through autumn to harvest sea salt, returning to a tradition that has been absent in Maine for 200 years. A 6-oz. jar sells for $8.99. It’s easy to imagine elegant jars of flaky Cape Cod sea salt perched alongside other vacation souvenirs.

Unfortunately the best months for harvesting salt overlap the Cape’s high tourist season. It is doubtful beach goers would be willing to share the shore with salt vats. The next time you slurp down a Wellfleet oyster or savor the briny undertones of a Cape Cod clam chowder, take a moment to savor our signature salt. The saltworks may be lost to time, but their memory still lingers in our salty air.