The High-Tide Lawyer

You’re traveling somewhere exotic, or maybe it’s not exotic, but it’s new to you. Somewhere you’ve researched, read about, perhaps had a fantasy of one day moving to, or even just driving through. Once there, you’ll often experience a short, magical moment of time. It happens after all the research is over, the traveling dirt has settled, the bearings have been gotten. You’ve got the comfy walking shoes and the right clothes for the temperature. Someone will walk by, maybe a thick accent echoes across a cafe, or a building seems somehow familiar. That’s when it hits you; the fantasy has become a reality. You take a quiet second to yourself, breathe it all in and think, “I made it. I’m actually here.”

Spring 1999

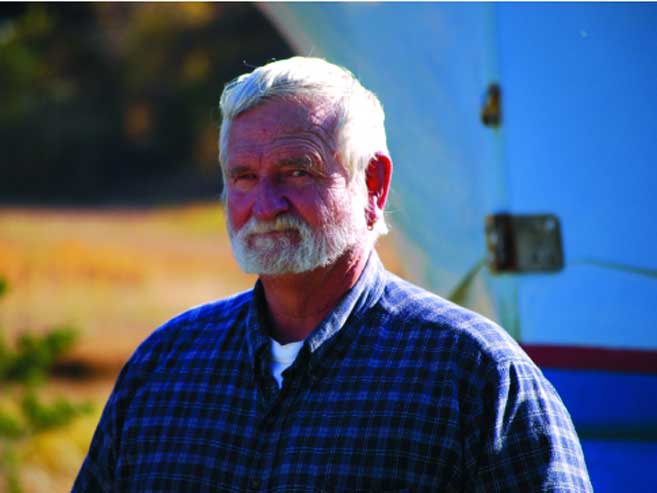

“Captain Bill!” a customer shouted across the boat-shaped bar. In he walked. A familiar character, albeit through cinema or books. Among the young marina workers and the lawyers and judges on their courthouse lunch break, in walked an honest-to-God captain. I had just moved to the Cape and it was my first week as day bartender at this harbor side restaurant. “Hello there, young man,” Captain Bill said, bellying up to the bar and giving the tiniest hint of a smile. Not enough of one to be accused of smiling for no good reason, more of a friendly glare. He had a steely demeanor and intense, squinting eyes that signalled to anyone looking into them that he had seen a lot of stuff, and had a million stories. His weathered face was framed by an Ahab-style white beard. Captain Bill was the Real Deal as far as I was concerned. It was at that very moment that it hit me: I’ve made it to Cape Cod. I’m here.

For the next bunch of years, Captain Bill would quietly wander into the bar; sometimes alone, sometimes with his wife Tess. After some time even a landlubber like myself felt at ease chatting with the two of them about the day’s events, the weather, the fishing. Nothing too heavy. After all, what could a guy from the suburbs of New York talk to a Cape Cod fisherman about? Through the years we remained cordial, but I eventually relinquished my bartending post, and with the exception of an occasional quick glance at a stoplight, I hadn’t seen much of Captain Bill.

Fall 2009

Having barely survived a crazy summer at the inn, I could only eke out a couple small articles for the fall issue of Edible Cape Cod. Now, with a lighter schedule, I started poking around for ideas for a more serious subject. I received an intriguing email from shellfisherman Les Hemmila of Barnstable Seafarms. “I’d love to read about Bill Korkuch, if you can get him to talk,” Les said. “He’s the guy with the humongous anchor in his front lawn on Commerce Road in Barnstable Village. He’s a steamer clam farmer known around town as the High-Tide Lawyer.” With the email came an attachment, which, on a double click, opened to a photo of the High-Tide Lawyer posed in front of an icy chest of oysters. It was Captain Bill! The next stop for me was going to be the house on Commerce Road with the humongous anchor in the front lawn.

Trying to interview Captain Bill Korkuch isn’t easy. At 66 years of age, he shows no sign of slowing down. At the time I was trying to track him down he was hunting moose up in Maine. When home, his life revolves around the tides. “Hi Tess, is Bill around?” I tried again. “Sorry Tom, he’s out working. He goes out about two hours before low tide,” she told me (low tide was at 6:00 am that morning—do the math). These kinds of phone calls went on for a couple of weeks, full of insane hours hard for a non-shellfisherman to dance around, and more moose hunting. Finally the stars (or technically the tides) lines up and I was granted a bit of time with Bill at his house. Walking around the anchor to the front door, I was greeted with a shout from the back of the house from Bill. “Only strangers use that door. Come on around!” He was happy to see me, but was definitely suspect as to what we were to talk about. Bill, Tess and I sat in the living room overlooking the marsh. “I suppose you want to know about the anchor,” he guessed. Back in 1979 the anchor had already gained Cape-wide stardom and was on the front page of many of the local papers. “Absolutely,” I responded, not letting on that I had a million non-anchor questions as well.

An attorney only dabbling in fishing, Bill was asked years ago to lend his muscle to free a friend’s trawling net that had gotten caught a couple of miles off shore. Not being one to hesitate to help a friend in need, Bill obliged. The net had gotten caught under 60 feet of water on the anchor of the Henry B. Palmer, a massive five-mast schooner that had gotten trapped in Barnstable’s icy waters in 1904. (The anchor was simply cut from the ship during the freeing process). Bill decided that he wanted the anchor for himself, and when he was told it was impossible, he recruited three friends, a small 30-foot boat riddled with leaks and enough chain to harness King Kong. “It took us a total of two weeks to drag that sucker in,” he regaled. “We’d drag it for a while, the tide would change, it would get stuck and we’d head in. The next day during a new tide we’d pump the water from the boat and start all over again. Took two weeks, but we got it in.” He looked down at the old newspaper clippings and smiled.

Born and raised in Hyannis, Bill moved north to Barnstable Village with his family when he was ten years old, and he never left. He helped his mother and father run what Bill believes to be the first B&B on Cape Cod (this was the mid-1950s, so that presumption could well be accurate). Bill’s grandfather was a Cape Cod fisherman, but his father was a carpenter. Noting Bill’s obvious love for the sea, I asked if he got the carpentry gene. Bashfully, he tells me no. “He did make this wonderful bay window,” Tess pointed out the one overlooking the marsh. “As well as the kitchen

countertop. Did you see it? It looks like a boat.” (Obviously the man can’t brag.) We went into the kitchen for a quick tour and I couldn’t help but note that my surroundings were 100 percent Cape Cod fisherman: a boat-shaped kitchen counter, cabinets with boat cleats for handles, and a beautiful harpoon over the hutch. Looking out the back door to the south side of the marsh sits an old, retired refrigerator van, and next to it Bill’s 30-foot working boat Seaquestor 2 named after his prior vessel, Seaquester 1. (“Seaquester” being an incredibly clever lawyer-turned-captain pun. A pun which yours truly missed until just this second.) “That’s my lobster boat, but I’m no lobsterman,” Bill clarified. “I take her out for tuna and cod.” For years Bill had someone else captain for him while he was chest deep in his general practice as an attorney. “I had an office in Hyannis and then one in Sandwich. I kept real busy.” Having graduated from Suffolk University and then Suffolk Law School, Bill’s priorities were his practice, but the salt air kept calling. So when the tide was right he would take off the tie and slip into the sea, and the nickname “High-Tide Lawyer” was born. After 30 successful years in the practice, and with Tess’ blessing, Bill followed his dream and traded in his law books for navigational maps, taking on the arduous task of becoming an official captain.

Although Bill spends a fair amount of time on the Seaquester 2, he spends more on his 17-foot Carolina skiff that he keeps docked just down the road in Barnstable Harbor. Once the owner of one of the first grants in Barnstable Harbor back in the 1970s (a whopping 12 acres, no less), Bill now shares his harbor with 40 other grant owners (although he tells us only about 12 are really “serious farmers”) and finds that scaling down from 12 acres to two keeps him busy enough. I asked him some technical questions—who he sells clams to, how many clams he can produce in the high season— and each question was put to a quick death. These are all trade secrets, and it is understood by the “serious” farmers that nobody answers such questions, not even over a few friendly beers, never mind in front of a guy holding a pad and pen. I asked Bill if I could join him on his boat one day and see how farming steamer clams works. “I mean, just to see…I’m curious…I don’t have to…ya know it was just a thought.” Bill was glaring at me with that suspect look again and took what seemed like an uncomfortable lifetime to answer. “You know, I’m a pretty private guy. I keep my business even more private. I’ll think about it.” Now I was a bit frustrated. I just wanted to understand what this guy does. I know it’s a lot of work. I know the hours are weird, and I know I love eating steamers, and so my curiosity was piqued. I also found his demeanor refreshing. When people learn that you want to tell the world about them, quite often they can’t stop talking. Bill, if you’ll ignore my not-soclever pun, kept clamming up.

I thanked Bill for his time and promised to harass him until he either let me see his clam farm or told me to “cast off.” One phone call after the next, Bill politely kept me at arm’s length, blaming rain, wind and unpleasant mornings. With my waders already in the truck, I got a call at 6:10 am. I slammed the phone into the receiver “Wind and rain?” I said feeling frustrated to be put off once again. “I thought Captain Bill was hard core?” I called him back at 8:45 to reschedule, again. “He’s not here Tom, he’s out working,” Tess told me. “Huh? Didn’t he say the weather was too lousy?” I asked. “It was probably too lousy for you to join him. Bill always goes out, no matter what.” Suddenly I felt like that dufus from the suburbs of New York again, but I really couldn’t blame Captain Bill. I’m no wimp. I can take a serious punch, but how was he to know that? Most people have a low threshold for discomfort. I understand the concern. “When Bill gets in, please tell him I can go out no matter what the weather. I’ll be fine.” Tess paused. “He was planning on taking you out tomorrow. It’s supposed to be 60 degrees and sunny.”

The dufus from the New York suburbs thanked her and hung up the phone.

“There they are! There are those damn ducks. Ya see ‘em?” I was on Bill’s skiff and we were heading out to the clam farm in Barnstable Harbor. The ducks, interestingly enough, cause the biggest nuisance to a clam farmer. “Look at ‘em!” Bill yelled over the roaring motor, his voice echoing across the desolate early winter harbor. “What’s the problem with the ducks again?” I shouted back. “They come up from the south once the cold weather hits the eastern seaboard! They’re opportunists, like pirates! We have to keep them away from the clam beds the best way we can or they can really hurt us!” The motor continued its wail as we zigzagged through a convoluted maze of low tide sandbars.

“Hop out,” Bill commanded, pulling the boat onto the farm’s edge. The weather was beautiful, as promised, but we wouldn’t be raking clams today. It was the slow season, which is a perfect time for maintenance work. Bill told me that November is typically the slowest time of the year, as clams simply don’t find themselves on the Thanksgiving table. “I’d like to tell Emeril Lagasse a thing or two! He’s always talking about turkey stuffin’ with sausage and cornbread. Anyone who knows anything knows that clam stuffin’ is the best! Emeril needs to take the Grinch out of Thanksgiving for us shellfisherman.” I helped Bill unload some nets, buckets, a clam rake and his homemade plow. “What’s that?” I asked. “We use that for plowin’ the farm. The plows you can buy I destroy in no time. I had to make this one from metal scraps and bike parts. It works like a dream!” A grand old grin hit his face. In spite of his rough and rugged demeanor, I witnessed many moments of sheer warmth and kindness from Bill over the years, and being out in the middle of the harbor, just him and me, I was comforted to know that he was showing that side of himself. His guard had dropped a bit. There were rows and rows of rectangular-shaped nets over muddy sand, and I asked Bill how the whole thing worked. The answer caught me by complete surprise.

What struck me by surprise is the dichotomy of professional clam farming. It is based around what could be one of the simplest sciences known to man, yet the sheer brawn and patience needed to keep this science altered to benefit all of us butter-dunking clam lovers is extremely difficult, often frustrating and quite often life threatening. Large, rectangular beds are cut out using a plow, or any other means chosen by a farmer. From there a net is dropped, stretched out and secured over the rectangle of muddy sand. That’s it. That’s how you grow clams. When the tide comes in, microscopic baby clams flow in and bury themselves in that muddy sand. And there they stay—living, eating, growing.

After a minimum of two years Captain Bill will come out to harvest the clams with clam rakes. Simple, right? Okay, cue the ducks. One problem with steamer clams is that they are a soft shell clam, and ducks can eat a steamer clam whole—shell and all—and go through a bed of clams like the research department at High Times at an all-youcan-eat pasta bar. They can cause massive destruction, flying in numbers that would make Alfred Hitchcock shudder. To make matters worse, when ducks pile up to the buffet, seagulls take notice and crash the party. It’s a nightmare and can cost a clam farmer a lot of money. (Curiously, ducks will only descend on a bed in a few inches of water. No more. No less. Once you scare them, ducks know their opportunity is over and won’t return. That is, until the next tide.) “And the moon snails!” Bill bellowed, “They’re a pain too! Moon snails will eat a clam by drilling right through the shell, which drills a bigger hole in my wallet!”

If a bed is ignored just a day too long, the sand can get up over the net and the net gets buried. If the net gets buried, clams will die. It all happens in the blink of an eye. In one tide a net gets buried, in another a bed gets wiped out from animals. Getting fresh nets down is time consuming—digging, plowing, stretching. But getting old nets up is simply back breaking. There’s no other way to describe it, even when it’s 60 degrees and sunny. Never mind when you are dealing with sub-freezing temperatures, high winds and the risk of actually freezing to death a mile and a half from shore because your motor wouldn’t start, or you lost track of the tide, or your anchor gave way. It happens.

On our way back to the boat, Bill pointed out some of his farm’s history. He showed me where he tried his hand at oystering, and also pointed out one of his few remaining quahog beds. “Ten years ago I lost close to seven million quahogs in one freeze,” he told me. Now knowing what the work entails, that news is positively heartbreaking. “After that I just stuck to what I do best— steamer clams.” We dragged everything back into the boat and headed back though the now-altered maze of sand bars. My time with the High-Tide Lawyer was over, and I could almost feel his sigh of relief. Bill quietly stared out to the horizon as we sped back to the harbor. Breaking the silence for the last time, I asked him about the best part of it all. “The sunrises,” he told me. “I’ve loved every one of them.” I thought about the brutal winters, the ducks, the digging, the plowing, the crazy hours. I asked about the worst part of it all. With a smile his squinting eyes looked straight into mine and he responded, “There isn’t one. I love it all.” And I knew he was telling the truth.