Back to the Future of Food

The Europeans to settle on Cape Cod landed here in the 1630s, after a harrowing journey across the Atlantic Ocean. They landed on the shores of Cape Cod, tired, and in many cases, malnourished. They quickly rowed ashore, rented a condo on a golf course, and went to the Super Stop & Shop for frozen pizza and nacho-flavored cheese chips. The wealthier passengers were picked up by shuttle and taken to seaside resorts to enjoy spa treatments and cuisine prepared by trained chefs. Others sold bottles of “Cape Cod Air” and assorted beach wares. The earliest Facebook post from a settler read, “Wife having her toes done. Cocktails by the pool. Priceless.” Back then you could get a caramel double shot latte and a bagel for just a few pence. The nightlife scene was thriving, and bands like the Rolling Stones and the Kinks were drawing good crowds at the local bars. Infused martinis were popular. Those were the days.

Discerning readers may have already noticed that I made most of that up.

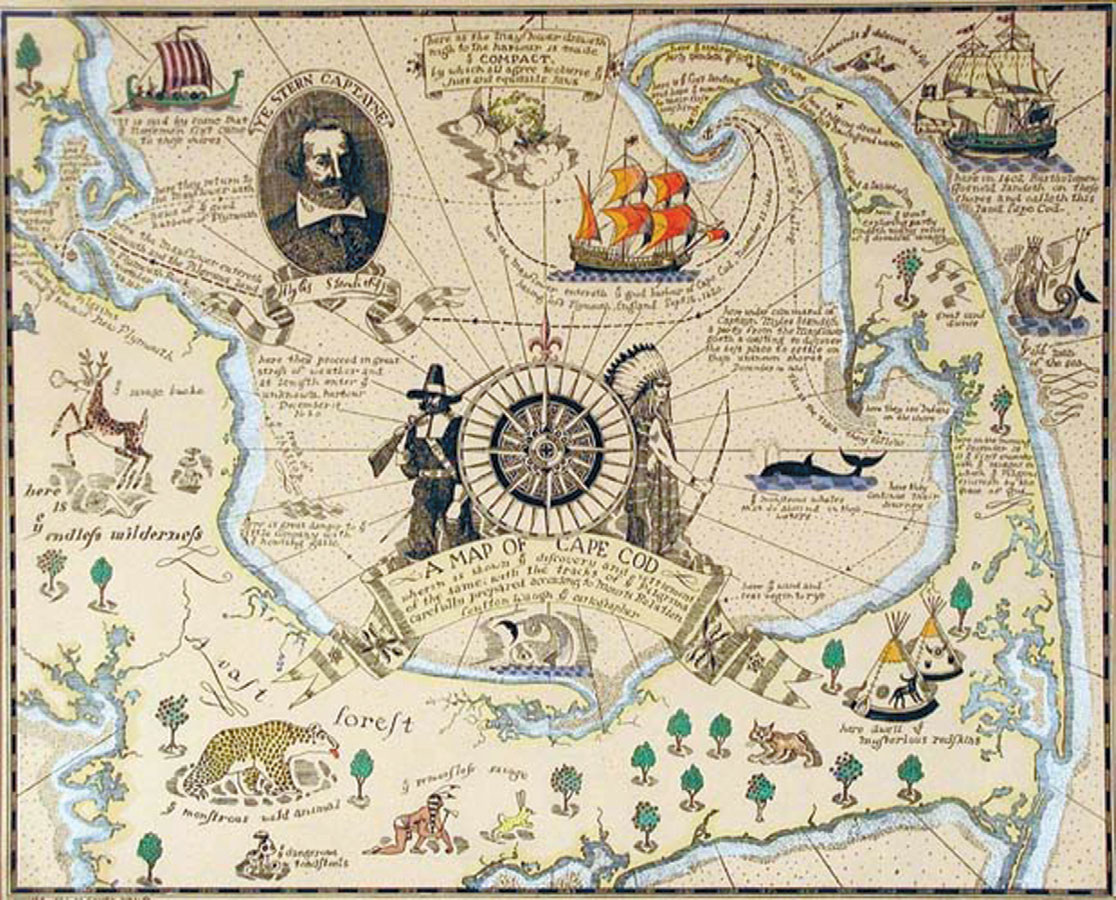

I often think about the settlers. We can’t imagine what life was like for them. The only thing here was the land and the sea. Nothing else awaited them, other than the stark struggle to survive. Where was the food? Shelter? Medical help? Maps? Roads? Infrastructure of any kind? There was nothing other than wild nature. They were driven by the will and the necessity to not die. To eat. They had to find a way to live, which is exactly what they did. Luckily for them, local Native Americans shared their knowledge of the land and the sea, and taught them how to grow corn. Today, it’s hard to imagine a place with no conveniences whatsoever.

One truth holds throughout time: people need food. Nourishing food. Life-giving food. You don’t need a jet ski, a gazebo, or a hot tub (although these things are nice to have); you need food. Life at its most basic comes down to the simplicity of eating, and having shelter. So much has changed since the days of the settlers. Life was a lot harder then, but there’s a new struggle occurring in our food system. It is no longer about finding enough food to eat. The new concern is how our food is produced and what’s in it.

Early settlers were fortunate to find fertile land that they could farm, or find wild blueberries and other indigenous plants. They were fortunate to live by a sea teeming with fishes that provided protein and nutrients. Shellfish was abundant. The Cape itself was and is a giver of life.

When I’m out on Nantucket Sound, fishing our weirs or clamming on the flats of Monomoy, I often feel overwhelmed with gratitude that somehow, food is here for us. When I see gleaming fish darting about in the waters, then landed on the boat, there’s a sense, an intuition about a God-made world. A world that is giving and bountiful. I feel connected to something bigger and deeper than anything I can comprehend: the miracle of life itself. I imagine the settlers roasting a fish over a wood fire and being thankful. I imagine after a hard winter, how amazing the warm sun of spring felt. When the plantings began to bear their first fruits, it had to be cause for rejoicing. There would be food to eat, and life would go on. The fish returned to the inshore waters, and there was plenty to eat. That is wealth: life-giving food.

When I was 19 years old, I left school and traveled to India, determined to find out the truth about life. I had noble dreams about truth and God. I lived there for four years in a rural area seemingly untouched by time. One of my jobs there was to travel to what was then Bombay (now Mumbai) to bring back provisions, food, medical supplies and whatever else was needed. The outskirts of Mumbai were flanked by miles and miles of slums. Millions of people lived in structures made of cardboard and assorted junk. There was no clean water to drink, and thousands of people—emaciated, sick, downtrodden—begged for food.

I stepped over dead bodies in the streets. I saw mothers clutching babies, desperate to find food. I saw children sitting in the street with flies covering their beautiful faces, starving. These images have stayed with me. The feelings of desperation, the look of hopelessness and starvation haunt me to this day. That is why I say that food is wealth.

In terms relative to today’s standards of wealth, I’m just a working guy. I scratch for quahogs, dig in the mud for clams, and work from sunup to sundown by the shore or out in the ocean, and I love it. The older I get, the wealthier I feel. I have everything I need, and more. I have incredible, healthy food and good shelter. I have friends and family. I can survive very well because of the bounty that is all around us. I don’t need more.

Kahlil Gibran was right. The very truth you search for is right in your own backyard. It’s in my garden, where squashes and cucumbers seem to appear overnight, where tiny plants turn into lavish tomatoes and delicious cilantro. Fragrant basil continually regenerates new leaves, and under the soil onions are quietly growing to provide us with food. It is amazing, really. These plants give everything to us. Their life is a beautiful sacrifice and an event of giving. The sunflowers stand tall like people, facing into the sun. Out on the water, the fish grow and mature and come into the sound and the bay to bring us their gift. Their lives are lost so ours can go on. It is the most humbling dance one can contemplate. I feel connected to nature, and the circle and miracle of life. That is wealth, to me.

What does it take to care for our incredibly bountiful part of the world? Anyone who reads the news knows that we have put our beautiful ecosystem in peril. There are too many chemicals, too much trash, too much waste. We take it for granted that nature will just keep giving to us, and we expect her to suffer our fertilizers, smog, slag and plastics happily. We’ve become separated from our ancestors. We’ve come so far with technology, entertainment and transportation that we’ve lost that incredible urgency and immediacy of life. This is the downside of our times. Despite all of the amazing achievements and inventions of mankind, we might overlook the basics with all the distractions of modern living.

Food is fundamental to life. A good meal is so enjoyable, but also necessary. We are incredibly lucky to be able to cook a delicious nourishing meal. Many friends have told me that Thanksgiving is their favorite holiday. It feels good to be thankful for the bounty, the harvest and the food that is placed on the table. It is a time of remembering our good fortune and the simple pleasure of eating together, and sharing with friends and family. It is a time to remember our ancestors and give thanks to all those who came before us and struggled to make a better life for future generations.

Modernization, science, and giant agribusiness have emerged in man’s never-ending quest for food. In the oceans, you hear terms such as “industrial fisheries” and “Big Box Boats.” The need to feed seven billion people is a tall order. I often wonder where all the food comes from, and how we are able to keep up with the demand. This is why people are concerned with factors such as climate change, oil spills, nuclear accidents, toxic waste, pollution and emissions from petroleum-fueled machinery. Some say we are tipping the scales by putting too much pressure on the environment.

Large agribusiness sees that there is a great need and demand for food. That’s true. However, the long-term health and environmental effects of growing more and bigger crops through chemical processes, pesticides, herbicides, and genetic altering are looming on the horizon. There are serious environmental and health concerns about these practices, not to mention the toxicity that ends up in our water tables and in our bodies. Fisheries have their own version of industrial food production. Giant vessels strip the oceans of many species, in search of a few. There is a great deal of waste in that process that has a devastating impact of the ocean’s ecosystem as a whole. Farm-raised fish is by and large an unhealthy yet lucrative industry. Fish are fed soy pellets, antibiotics, hormones, and are genetically altered to grow unnaturally fast. This kind of fish has little of the health benefits that a wild-caught fish brings to the table.

Man has gone from foraging, farming and catching food to sustain life, to a new view of food. Food is a commodity. Supply and demand. Food is big business. We are eating matter, but not necessarily food.

Food is now really separated into two categories: food for basic survival, and food as a luxury item. There’s caviar, and there’s bologna. Foie gras and meatloaf. Champagne or hooch. We’ve become a society that consumes food according to our ability to purchase, rather than what we have around us that will sustain us. It is a seismic shift in our approach and our perception of food. The other, less obvious concern, is the quest for inexpensive, mass-produced foods. When food becomes industrialized, it loses nutritional integrity as well as environmental responsibility. Produce may be bright green, or last for weeks in the refrigerator, but what chemicals and pesticides are in it? Farm-raised fish may look good on the plate, but how was it fed?

I think back to the settlers, and the Native Americans. Life was harder, but there was a purity in the food. The food was not shipped in from an Asian shrimp farm. They utilized what nature provided in the vicinity of where they lived. Cape Cod soil and Cape Cod waters provided what was needed to sustain life. Cape Cod is a fertile, abundant place in the world.

When I see a sign or an article that says “Support Your Local Farmer” or “Know Your Fisherman” I do not see a nice trendy idea designed to market a dream of sustainability. I see a call to remember the bounty that is right here, on Cape Cod. It’s a call to reconnect with our ancestors and embrace the natural bounty and methods that are all around us, and most importantly, be thankful for that. Trust that. Food is fundamental. Healthy food is life giving, necessary and nourishing. It never was a trend. Food has always been the foundation of life.

Russell Kingman fishes the Eldredge family weirs in Nantucket Sound, helps run Cape Cod Community Supported Fishery, and is an independent wild shellfish harvester in Chatham.