Fake News and Spinach Pie

The Alternative Facts

While researching this article, trying to find something the least bit interesting about spinach (besides the fact that nothing is more delicious than a garden-fresh spinach pie), I discovered something beyond belief. Every Google search, food blog, nutritional site and even book on the subject of spinach restated the same revelation. They said that in the 1830s a German chemist studying the iron content of certain foods ascertained that spinach contained 3.5 grams of iron per 100 grams. Nothing extraordinary, but while transcribing the results from his notebook, the researcher misplaced the decimal point, writing 35 grams, and giving spinach a tenfold increase in its iron value.

The error was brought to light in 1937, but not widely publicized until T.J. Hamblin wrote about it in the British Medical Journal in 1981. With such well-respected endorsement of information from academia, I was stunned that I had never heard about it. Furthermore, they said that there had been a 30 percent increase in spinach consumption during the years that followed the misplaced decimal incident, boosted by E. C. Segar’s cartoon creation Popeye the Sailor. If you ask just about anyone today what it is in spinach that makes Popeye strong, I’m sure they’ll tell you it’s the iron.

All that coaxing by my parents, the news media and by Popeye himself to eat my spinach was all a hoax. My hopes of spinach being a wonder food and writing an article about it were dashed. I had just wasted weeks of research, or so I thought.

I decided to do a little fact checking. Article after article reiterated the flawed findings touting the super power of spinach. The first clue suggesting something was amiss: I could find no information on any German chemist named E. Von Wolf. Turns out they were referring to a German scientist Dr. Emil Theodor von Wolff (1818-1896) who had most likely provided chemical analyses of burnt plant materials for the determination of iron content (dried plant matter contains much higher concentrations of iron that fresh plants). This could have been the mix up, not a decimal point. Second, I discovered that Segar chose spinach as the source of Popeye’s power because of its high vitamin A content, not iron, in an attempt to promote a healthy diet for children and their parents alike during a time when “greens” were equated with cow food.

Spinach does contain iron, but only twenty-five percent of the iron in spinach is “available” in a form that is usable by the body. This is caused by the effect of oxalic acids (a major component of spinach) on iron availability. Oxalate binds with calcium in the digestive tract, becoming an insoluble salt that cannot be absorbed. Spinach not only contains iron, but a healthy dose of it, and combining the consumption of spinach with certain other foods, such as tomatoes or citrus, changes the negating affect of oxalic acid’s iron absorption. Lightly cooking spinach also breaks down the oxalic acid molecules without causing too much loss of the vital nutrients. The vitamin C in such other foods also blocks the oxalate from binding to calcium, encouraging further absorption. So, lo and behold, I even found more reason to get back to my original reason for writing this article: spinach pie!

Spinach pie is all about fresh veggies, and that motivates us to set aside a portion of our garden just for its component ingredients. Creating a “spinach pie” garden is quite basic: spinach, scallions and dill. The best thing is that these ingredients are very early-season crops, and at the same time, late-season crops, yielding an almost four-season harvest. When it’s still late winter with only a touch of spring in the air, and you are itching to go out and start planting, that’s the time to plant your spinach pie garden. All three vegetables like the earliest of spring planting; six weeks before the last frost is not too early. They all like the same soils with the same watering requirements when fertilized with rich, well-rotted manure.

When market gardens thrived around the edges of Boston and other east coast cities in the late 1800s, spinach and scallions were both very popular and valuable crops. Acres of small market gardens were filled with them. Their profitability stemmed from the fact that there is hardly a time during the year when they could not be grown, or find ready sale in the city markets.

The cultivation of all three spinach pie crops is the same. Soils are prepared and seeds sown as early as the soil can be worked in spring. The ground is pulverized, all stones removed and raked flat and smooth (a requirement for the most productive return). For fall harvest, spinach seed is sown in August, and for winter and the earliest spring crops, it is sown in September and early October.

The fall crop is the most difficult, as early- to mid-August sowing is tough. At that time of year it is usually so hot and dry that seeds refuse to germinate unless extra precaution is taken at planting time. Seeds should be well tamped down; walking down the row after seeding works just fine. Germination is best between 45 and 75 degrees and it takes seeds seven to twelve days to germinate in optimal conditions. Keep the ground well watered (drip irrigation is better than overhead watering) and cultivated and free from weeds. Spinach has a deep taproot and a shallow yet extensive branching root system, with most of its feeder roots in the top few inches of the soil. As a result, spinach appreciates a side dressing of compost occasionally.

Excessively high temperatures can delay germination. I’ve found an easy way to help the spinach seed to germinate during this hot dry period: plant your rows east to west instead of the traditional north to south. Plant your scallion rows on the south-facing side of the garden. When harvesting the early crop, leave a few rows to overmature in rows about a foot apart and plant your August sowing of spinach seed on the north side of each remaining row of the overgrown scallions. This way the large scallions help to keep the ground a bit cooler for germination and shade the spinach in its early growth. Later, when the weather cools, the scallions can be pulled. Some varieties will form bulbs that can be used like summer onions. Should the plants come in very thick, they may be thinned September through November.

In milder years, the remaining main crop usually winters over without much loss if lightly covered with coarse litter or leaves. The crop can then be cut in very early spring, well before your spring sowing.

Market gardeners of old often grew their onion crops from seed, preparing their own “sets” for early planting. It is what I prefer to do. I seed deep flats in early fall, setting them out on the ground under a slatted bench and covering them with straw for the winter. In late winter I uncover them or bring them into the cold greenhouse as soon as I can work the ground. I plant them in well-prepared beds alongside seeded rows of spinach around the time daffodils set green flower buds and the peepers return for their second heralding of spring. I seed the dill at the same time, as it likes cold weather. Once it germinates, it easily endures a light frost.

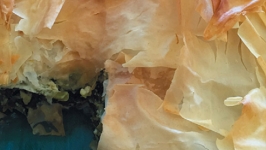

I just love spinach pie, especially straight out of the garden—really the only way it should be prepared. You want fresh, because anything less will wilt down and lose that crunchy texture as well as much of its nutritional value. You need nice, big, stemmy spinach, too. I don’t blanch it first like many recipes will tell you to do. Rather, lightly crush it in a colander, letting any excess water drain through. Then a couple of bundles of freshly-pulled scallions, a really big handful of dill, the best feta cheese you can find and farm fresh eggs.

Spinach is not only loaded with vitamin A, but iron, vitamin C and folic acid as well. So, turns out, Popeye wasn’t lying when he sang “I’m strong to the finish ‘cause I eats me spinach!”