Aquaculture: It's Not Just for Shellfish

Chatham Kelp is growing seaweed to satisfy culinary cravings and help preserve the maritime culture

Motoring out into Nantucket Sound from Stage Harbor in Chatham on a brisk, windy, but cloudless spring day, Chatham Kelp co-founder Jamie Bassett issues safety tips to the two visitors on board the 18-foot Carolina skiff. Chief among them: stay seated. There’s little chance of a mutiny. Cori Egan is focused on protecting her camera lenses and I struggle in vain to keep my notebook dry as swells that weren’t apparent from the shore smack into and over the side of the boat.

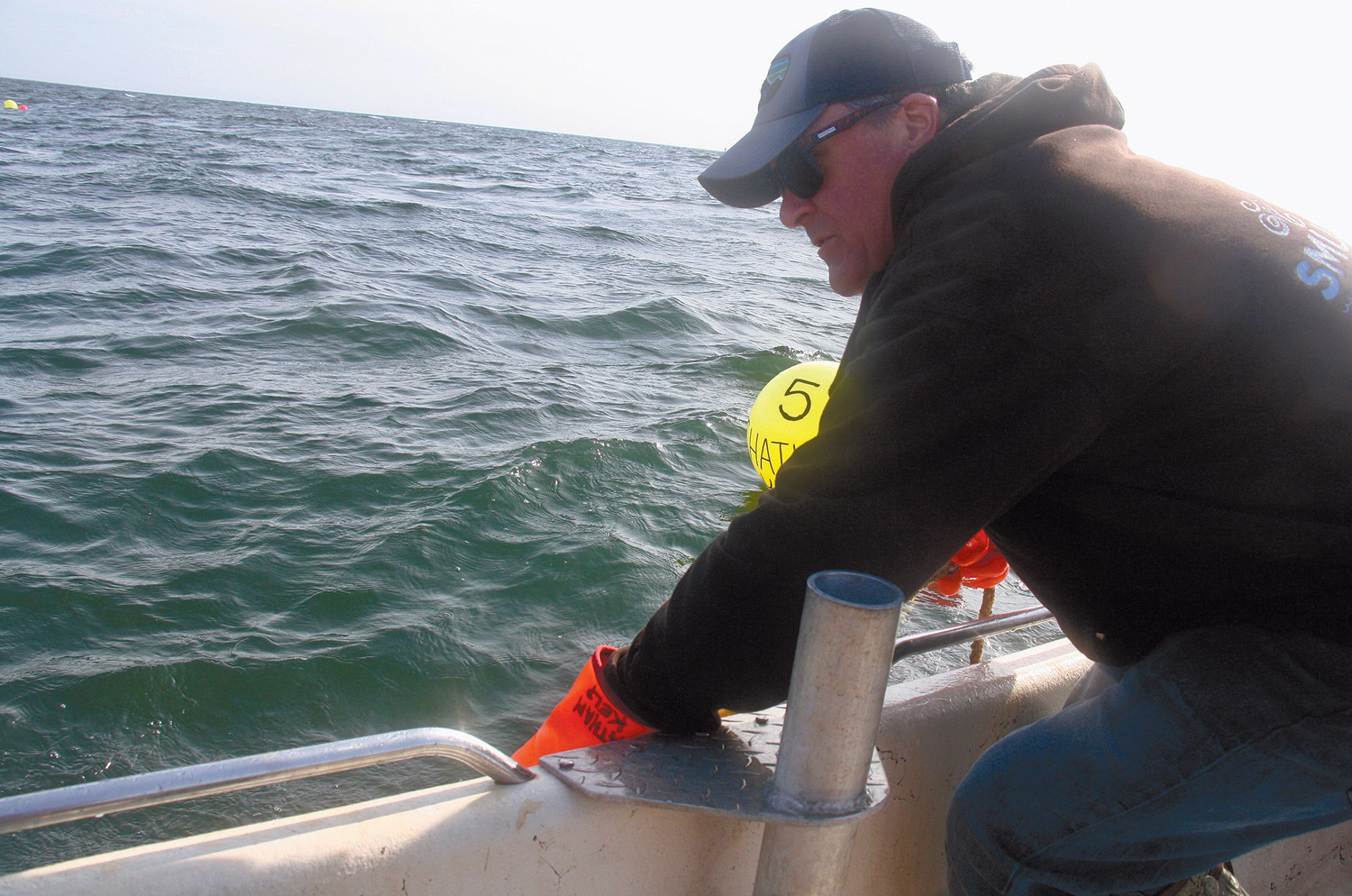

It is the beginning of harvest season, but Bassett and his partners, Carl Douglass and Richard Curtiss, have not yet begun to bring in their first season’s crop. Today they are collecting just enough kelp to deliver to Michael Ceraldi, chef-owner of Ceraldi in Wellfleet, who will use it to begin testing recipes for two upcoming dinners at the James Beard House in New York highlighting Cape Cod ingredients. When we reach the farm, apparent only as bright yellow buoys bobbing on the water’s surface, Bassett cuts the motor. Curtiss reaches over the side of the boat and pulls up a line draped with near-translucent yellow-brown strands of what look like long, slender lasagna noodles. They cut off what they need and we head back in.

Back on land I ask to try a piece of the kelp. It is much milder than I had expected, bracingly fresh, with an almost bouncy crunch. Later, Michael Ceraldi tells me that it has amazing gelling properties, and turns a bright, vibrant green when you blanch it. If it is blanched or dried, then frozen as soon as it is harvested, the sea plant can be kept for several months and used in the kitchen in a multitude of ways. So although it is a winter crop, diners on the Cape can enjoy it now.

Kelp farming was first practiced in Asia and is slowly catching on in the US. Aquaculturists in Maine—fishermen and women looking to diversify, as well as entrepreneurs with an eye toward sustainability— have been growing seaweed for about a decade. Growth in Massachusetts has been slow so far, but, says, Joshua Reitsma at Woods Hole Sea Grant, “The interest is definitely there,” and it has picked up in the last five years. Chatham Kelp is the largest commercial kelp farm in Massachusetts and the first stand-alone permit-issued farm. According to Christopher Schillaci, at the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF), all of the previous seaweed permits were issued to existing shellfish aquaculturists.

With fisheries under siege from a multitude of threats—from warming waters to overfishing to changing quotas on existing species—the founders, all longtime Chatham shell fishermen, were looking to diversify their business and generate income during the slow winter months. It was important to them that the business be sustainable and, says Douglass, “We wanted to do something in the ocean.” Initially, he wanted to start an oyster farm. When that didn’t work out he turned his attention to seaweed.

Where seaweed was once dismissed as a nuisance—something to be stepped over at the beach or the last thing you would want to pull up on your fishing line—people are seeing it in a new light. Kelp farming offered an attractive option for many reasons. Sugar kelp is planted in November and harvested by May, so there is no conflict with recreational fishing, boating or other commercial fishing activities. It is also a zero-impact crop that doesn’t add anything harmful to the environment. DMF’s Schillaci explains in an email, “Since kelp does not require fertilizer or other additives and actually uptakes excess carbon and nutrients from the water, kelp culture is generally considered ecologically beneficial.” He tempers that with the caveat that at “current industry scale those benefits are likely to be very localized.”

From a culinary perspective, sugar kelp is both nutritious—high in fiber, iodine, iron, protein, potassium and vitamins—and tasty, though it may be an acquired taste for some. Though a lot of us are most used to enjoying it with sushi, “The good thing with seaweed is you can use it in a ton of different ways,” says James Hackney, executive chef at Wequassett Resort and Golf Club in Harwich, a Chatham Kelp customer. “It adds new texture and massive amounts of flavor, and it’s right at our doorstep.”

It took the Chatham Kelp partners three years from planning to first harvest. They learned everything they could about growing sugar kelp, drawing on experts in New England and their own research. They also had to present their plans and receive approval from nine different committees, including the DMF, Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management, Department of Environmental Protection and the local harbormaster before they could get the permits they needed to start. “Kelp is a sustainable resource. We were able to get positive backing from the Department of Marine Fisheries for an area to put kelp in, but there couldn’t be any eel grass on the bottom and we had to make sure that there were no other conflicts,” Bassett explains. “So they permitted us a specific number of lines.”

They chose their site, about a half-mile off Harding’s Beach, because it is close to shore, deep enough (at least 15 feet), protected from northerly winds and, he says, “We’re as close as possible to the fresh flow of the Atlantic Ocean.” The kelp farming season coincides with the period when 60% of the North Atlantic right whale population returns to this area to feed, and Schillaci explains that the farm equipment is similar to fishing gear that has been banned in from Cape Cod Bay to protect the whales. But the farm, on the south side of Cape Cod and Buzzards Bay, is far enough from the whales’ usual habitat that it does not pose a risk.

The Chatham Kelp team worked with GreenWave, a Connecticut-based organization that helps launch new restorative ocean farms and build demand for the farmers’ crops. Douglass and Curtiss say Scott Lindell, a biologist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who is leading research efforts into large-scale seaweed farming, also “was helpful getting the ball rolling.” Chatham Kelp got all of its seed from GreenWave. It comes on string wrapped around PVC pipes that has been inoculated with kelp spores and incubated in the hatchery until the kelp blades grow to two millimeters in length.

Kelp lines on a farm run horizontally between two buoys, one to two meters below the water surface, depending on the water clarity (Chatham Kelp’s are seven feet below). Brightly colored floats are attached to make it easy to find them. In their first season Chatham Kelp seeded five 200-foot lines. Their 50-acre farm is permitted for up to 350 lines next year. To seed the lines a farmer detaches one end from the buoy, feeds it through the center of a PVC pipe, then reattaches it. Then a farmer drives the boat parallel to the line, letting the string unravel and wrap around the line. When he reaches the other end, he ties the seed string to the line and removes the now empty pipe from the line. As the kelp grows, its root structure attaches to the larger kelp line. The Chatham team experimented with lines, using both hemp and nylon. The nylon was slightly more durable but they say they like using hemp because it is sustainable.

The team put the lines in the water on December 10. Ideally, says Douglass, they should go in around Thanksgiving. GreenWave’s Jill Pegnataro, farm manager and hatchery tech; Michelle Stephens, hatchery manager; and Ashley Hamilton, science lead, came from Connecticut to help them seed the lines, and visited monthly to help monitor water quality, collect growth measurements, and provide other technical assistance and training.

The chefs were waiting for the crop before it was ready to come out of the water. Anthony Cole, executive chef at Chatham Bars Inn, and his chef de cuisine went out to the farm and took some early samples before the harvest began. “It was really delicious,” he enthuses. “It’s so good for the ocean. [They’re] creating a little rain forest in Stage Harbor.”

Because kelp is a winter crop, and many of the company’s customers are seasonal businesses, there’s a bit of a lag time between when it is harvested and when it will be consumed. From the time it came off the boat, local chefs began experimenting, determining the ways that worked best for them to preserve and cook with the sea plant. In the Chatham Bars Inn kitchen, Cole and his staff tried blanching then drying it and blanching and freezing it. Cole is mixing the sea vegetable with lettuces they grow on their farm for salads, among other uses. Look for it on the Beach House menu, which specializes in fresh, local seafood. The chef says diners are always looking for healthier dishes. “This will have a more prominent, center-of-the-plate place.”

Ceraldi, who has foraged for kelp in previous summers, discovered Chatham Kelp on Instagram and began a dialog with the team last winter. The chef has built his restaurant, which features seven-course set menus, around Cape Cod ingredients. “Anything from here is exciting, something new for me to use,” he says. For the Beard dinner he dried some of the kelp to make nori and pureed some to make a gel. He served both forms with sliced and ceviched scallops. Experimenting in his kitchen he also made vibrant green, lacy kelp chips. When he received his full delivery for the restaurant he dried some and froze some to use throughout the season. When the fresh kelp is dried, he says, the “seaweed flavors really pop.”

Wequassett’s Hackney says cooking with local seaweed is “intuitive to what we do, use [ingredients] at the peak of seasonality or preserve and use them through the season.” He poaches the Chatham kelp to serve in salads and dries it to use as “a salt-like condiment… slip it in for the umami factor.” He also pickles it, uses it in sauces, “even in a beef dish to give it structure.” He tried steeping it in milk to make ice cream, but based on the tone of his voice when he described the finished dessert, I wouldn’t hold my breath waiting to see it on a menu.

In their first season the team harvested around 300 pounds of kelp. For the long term, with more lines in the water and a greater yield, “We’re hoping maybe we can also employ people and create jobs,” says Bassett, “and maintain a maritime heritage that is very important for coastal communities.”

Chatham Kelp didn’t come close to breaking even this year. But that wasn’t the point. Says Curtiss, “We learned a lot so we’re very happy.”