Clamming up on Nantucket Shoals

The clam chowder you love to eat may be a lot more complex than you think—and not because the chef added smoky bacon or fresh thyme. The Atlantic surf clam that is its main ingredient has a complicated fishery that bedevils the independent smaller fishing businesses here on Cape Cod. But these local fishermen also have the chance to lead the way toward an appreciation of a fresh take on an old favorite.

The Goody Hallet began its life as a dragger, plying the ocean off the New Bedford coast, but for the past four years this renovated 85-foot fishing vessel has been busy harvesting surf clams from the rich fishing grounds of Nantucket Shoals for fisherman Scott Nolan and his family.

“She is so much more than a boat to us,” says Nolan. “We put everything into her.” For nearly seven months he and his son Max, also a fisherman and captain, drove down to the shipyard in New Jersey every Monday to spend the week working on her. “We begged, borrowed and stole all we could to fix her up,” he says.

Nolan’s wife Jodi remembers one hot summer day, shortly after Nolan recovered from complicated hernia surgery that had laid him low for a month. “We got down to New Jersey and there she was, half-finished, half not a boat at all, the tarps blowing in the wind. And I thought, what have we done?”

But by the next Monday, Nolan and Max were back at work, rebuilding the vessel that would provide a livelihood for their extended family here on Cape Cod.

Nolan, his wife, and son were willing to risk everything for a fishing boat because he absolutely loves what he does. “Not everyone can say that going to work feels like a playoff game. Every day I’m that pumped. I love fishing, and I really think sea clams are incredible: healthy, abundant, flavorful.”

Atlantic surf clams are a large variety of hard-shell clam found in deep water, akin to their shore-centric cousins. Unlike some of the smaller clams, however, the belly in a surf clam is not eaten. After the belly is removed, the foot—or “tongue” as the fishermen tend to call it—is cut out and made into strips for frying. The remainder of the clam meat (mostly the abductor muscles that close the shell) is minced for chowder or sauces. Nolan wants consumers to know, however, that there is a better way to enjoy these bivalves: fresh.

“The livies are the way to go,” says Nolan. “The meat is fresh and delicious, and you can cut it up and saute it, or eat it raw. There is nothing like the taste of a live fresh sea clam, especially from our own Nantucket Shoals area.”

Jared Auerbach, C.E.O. of Red’s Best Seafood, who calls himself the biggest fan of surf clams around, agrees. “It’s an amazing seafood item. So tasty and affordable.” Red’s Best is a distributor for fresh clams to many local restaurants, especially in Boston’s Chinatown district. “These are incredibly delicious, sushi-grade clams.” And he adds that dealing with local fisherman is good business for everyone.

Being able to work with wholesalers for this live market is something Nolan has had to fight for, and fighting for his fishing business is nothing new to the sixty-year-old veteran fisherman. “I fish out of New Bedford, and that is a tough town to work in. You have to be ready to fight every day of your life. Fight physically and fight mentally. And fight the big guys.”

The big guys are the processors, mainly based in New Jersey, the vertically integrated conglomerates that own the boats, the processing plants, the equipment and the right to fish for the clams themselves. The sea clam fishery is managed by something called an Individual Transferable Quota system, a kind of catch-share system in which regulators set a total allowable catch for a fishery and then allocate quota shares to individuals based on historical catch, which can be bought, sold, leased and transferred. Originally this concept seemed to hold promise that small-boat fishermen could thrive. But the opposite has happened. The deep pockets of big processing companies were able to obtain and purchase massive amounts of the available quota, leaving small businesses like the Nolans out of luck. “There are two other independents like me,” he says, “and we basically work for the big companies.”

Nolan came from a fishing family in Rhode Island, one that his own father sought to escape. “He would be taken out of school to go scalloping and he hated it. He couldn’t wait to leave.” His father first went into the navy, then to college and ended up working for U.S. Steel in the Midwest, where Nolan was born. But Nolan ached for the seafaring life his grandfather had enjoyed, so he came back to New England, went to the University of Rhode Island, and then began fishing for clams.

He married once and had two boys. One of them, Max, followed in his footsteps and now runs the boat for him. After his divorce, Nolan left the fishing business for a while, opting to captain whale watching boats out of Provincetown. “I loved it. The people were great to work with and it was fun. But it was hard to make a living,” he says.

Meeting his second wife, Jodi, who comes from an old Cape Cod family (her great-grandfather Nickerson was the shellfish constable in Orleans), inspired him to get back into fishing. “We talked about it and thought we could come up with a way to make it work for our family.”

“We had it all worked out, we thought,” he says. “We bought the Goody, fixed her up, worked hard to get her operational. I found independent processors who might pay a little more for the clams and I could get the quota tags from the Trust.” The Cape Cod Fisheries Trust, part of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance, is a non-profit permit bank designed to provide quota at reasonable rates for local fishermen. “We rely on the Trust and the Fishermen’s Alliance for the collective clout they can command. It helps us have some control over our destiny,” Nolan says. This system should allow small boat fishing business to compete in the marketplace, but it didn’t quite work out that way.

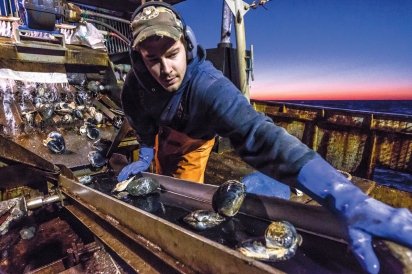

“We forgot about the cages,” Nolan says. His vessel is outfitted with a large steel dredge that, once they are 100 miles offshore on Nantucket shoals, is lowered to the ocean floor. An eight-inch-wide hose blasts water in front of the dredge, churning up the clams, and then the dredge scoops them up as it is pulled along the seabed. The dredge is lifted up onto deck, the clams are tumbled along conveyor belts into a hopper and shaking machine and then ultimately stored in large wire crates or “cages” in the center fish-hold. The cages are owned by the processing company, and they’re how the clams are transported from boat to plant.

Nolan could get the quota tags, catch the clams, and find a different way to sell his product, but the large companies denied them the ability to use their cages … unless the clams were coming to them. “And cages are expensive,” says Jodi. “The Goody Hallet holds 28 cages on board, and if we were to buy new ones of our own it would cost more than $50,000” [total].

Nolan isn’t ready to give up the chance for more independence in his fishing business, however. He continues to negotiate extensively with the large companies to be able to clam year-round on twice-weekly, 48-hour fishing trips and sell his clams to other wholesalers. But sometimes battling with processors ends up being more demanding than the actual fishing.

“You just want to be able to have some freedom and independence, you know? I love fishing and feel lucky. You want good trips, and let’s face it, every time you come back alive it’s a good trip. If you have a hold full of clams it’s a great trip. I’m proud that I’m feeding people and that I’m catching something people love to eat.”

Nolan returns to the suggestion that we all should try something new with our old standby clam. “You have to try them fresh. You have to taste what a real clam tastes like and then you will know why I fight for the right to catch them.”

Scott Nolan’s favorite way to prepare sea clams

Shuck fresh sea clams and squeeze bellies out. Rinse thoroughly.

Slice the tongue into ½-inch strips

Add 2 tablespoons butter and ¼ cup olive oil to large skillet on medium heat. To make it like Nolan’s grandmother would, use a bit of salt pork instead of the olive oil.

Add one clove of garlic, minced. Stir.

Add clam strips and sauté for about 5 minutes.

Top with chopped fresh chives or scallions and plate it with starch of your choice. (Linguine cooked al dente is great!)