Burping Sheep & Orange Egg Yolks

Marcel Moise grows barley sprouts in Ottawa, Canada as a superfood for his beef cattle, year round, in a greenhouse. Barley grass is considered the most nutritional of the green grasses, containing an abundance of nutrients unsurpassed by any other type of grass. The cattle live in the greenhouse too, providing the warmth, carbon dioxide and methane to grow vigorous sprouts. In turn, the sprouts are a nutrient-rich food—better than grain, better than hay—for the cattle. Moise says that the heat produced by eleven 1000-pound calves warms a 2700-square foot greenhouse; they only used supplemental heat when it was 55 below zero with the wind chill. The cattle keep the temperature at one or two degrees above freezing. As soon as Moise’s calves can eat 12 to 15 pounds of barley—at six to seven weeks old—he takes them off milk and solely feeds barley grass from that point on.

The barley is germinated in trays with no soil, placed on flat sheets of plastic, and watered and fed by misting nozzles run at intervals from a system using a timer, a pump and a fan. Moise recommends calcium-based fertilizer instead of nitrogen-based. The roots, stems and stalks are fed to the calves.

Barley grass has been shown to increase the overall health of cattle through better digestion of hay and grain. The sprouting process makes the barley, wheat, or whatever grain you’re using, become essentially more vegetable than grain. Grain changes the pH of the rumen to an unhealthy acidic level, where a detrimental type of bacteria flourishes, and can cause the need for antibiotics. Better digestion means fewer or no antibiotics needed to regulate the bacterial imbalances in the rumen, and it also lessens the creation of methane by gut microbes. Chickens and other birds, on the other hand, were designed to eat whole grains; sprouts just enhance their overall health by adding leafy greens.

As I come across more and more information that suggests cows and sheep emit a massive amount of methane through belching, I just couldn’t pass up getting sidetracked and sharing fantastic headlines like this one from Wales: “Upside-down Sheep Narrowly Avoids Exploding.” Upside-down sheep are unable to burp out their stomach gases, which can build up until they explode. It may be true, but it is quite funny, this burping thing. Personally I have never heard my sheep burp, they must be talking about methane and other gases emitted when animals bring up food before chewing their cud.

Weirdly enough, Australian scientists are hoping to breed sheep that burp less as part of an effort to tackle climate change. Along with carbon dioxide, methane is a greenhouse gas. Contrary to popular belief, it’s odorless—that stinky smell we blame on methane is most often hydrogen sulfide, the stuff you smell at low tide. There’s much less methane in our atmosphere than carbon dioxide, but according to the US Environmental Protection Agency, methane is more than twenty times more effective at trapping heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. The Australian researchers are working on several means of reducing methane emissions by changing the microbes in the gut, altering their diet and changing the genetics of animals. But Dr. Roger Hegarty of the Australian Sheep Co-operative Research Centre admits that, “Methane is the exhaust from livestock and—just as you can’t put your hand over the exhaust pipe of a car and expect it to keep running—we’re treading carefully.”

About 16 percent of Australia’s greenhouse emissions come from agriculture, and 90 percent of that is the methane that comes from the rumen of sheep, cattle and goats. Trials of new diets designed to improve ruminant animals’ digestion, and hopefully help reduce global warming, seem to be proving the most successful. If ruminants are fed the finest, most tender and digestible greens, they don’t even have to burp the food up and re-chew it in their cud. Studies are showing that feeding lush greens, clover and alfalfa instead of grain reduces methane emissions by 25 percent.

Getting back to barley sprouts and other hydroponic feeds, research is showing that the protein content is more nutritious than that of commercially available feed mixes. It is also more digestible, and the process of growing it will produce five to ten times more feed volume.

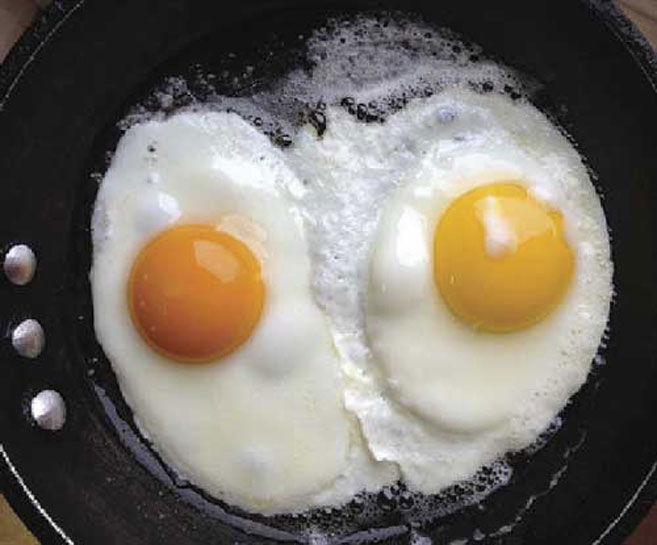

After reading Moise’s article and watching his YouTube video Barley Sprout Super Food for Livestock, I couldn’t help but try it myself on a small scale for my chickens and sheep. What great addition to winter feed (and year-round feed for non-free range chickens and livestock)! A lot of people are raising chickens these days, but not everyone can let their backyard flock roam or has access to surplus vegetable crops. Since happy chickens lay more eggs, and chickens eat sprouts, sprouted green fodder is a great substitute for free-ranging, producing much more flavorful eggs with bright orange yolks, and very healthy animals. Eggs produced by hens that can’t free-range just don’t look or taste the same. Just because an egg or meat is local doesn’t necessarily mean it’s as good as it can get. If the animals aren’t free-range, eating fresh grass and greens (which is particularly difficult here on the Cape), feeding this hydroponically-grown green fodder is a great substitute.

There are fairly inexpensive fodder systems available that can produce enough food for large numbers of animals in a relatively small space, and mini systems that can produce about 125 pounds of fodder, enough to feed 1000 chickens daily. But for smaller amounts, one can use regular self-draining plant trays for green sprouts or even food grade five-gallon buckets for non-green sprouts, easy enough for the small yard farmer. Very little light is actually needed for either type of sprouting. Like sprouting grains for human consumption (wheatgrass, beans, alfalfa, etc.), growing fodder is relatively easy and has a quick turnover from start to finish. The typical sprouting time for fodder is six to eight days, depending on what stage of growth you want to harvest at and the type of animal you are feeding. Many different grains can be used, like wheatgrass, barley, oats, etc. Barley is the most popular.

I first sprouted rye seed, as I happened to have some on hand. It was ready for eating in five days. Some of my sheep loved it from the first time I presented it to them and others hesitated but eventually loved it. Same with the chickens. I’ve got barley germinating now and I can’t wait to see how they like that. Out of six pounds of seed spread half an inch deep in trays, I should get about 22 pounds of fodder. That’s a four-fold increase in feed weight!

The basic method of growing fodder is as follows:

• Soak the sprout grains or seed mix for about 24 hours

• Use sterilized buckets and containers that are food safe

• Drain and spread into shallow trays that have drain holes

• Water a couples times a day, keep moist and drained for the duration of growing cycle at a temperature range of 55° to 75°F

• Harvest at the desired stage of growth and feed immediately to the animals

Sprouting fodder is a low-cost source of high quality feed—better feed than you can buy at the store. Finding the grains in bulk for sprouting may be the big challenge. Fedco Seeds is one nearby mail order source available if local feed stores don’t carry the grains you want. “Robust Barley” is the variety commonly used in barley sprouting in feed systems, but other grains like wheat and oats work, too. With the increasing price of feed, growing green fodder sprouts may be a worthy investment of our time, a great solution to limited grazing land and a step in the right direction towards maintaining sustainable agriculture here on Cape Cod.

Veronica Worthington is an organic farmer who grows heirloom vegetables for market and breeds heritage sheep for wool in West Dennis.