Sustaining Sea Scallops

*EDDY Awards 2016 Winner for Best Story, Environmental or Sustainability!

Could cooperative research be a new model for New England fisheries?

They call them pearls of the Atlantic. Glistening with pan-seared succulence on fine dining tables worldwide, the sea scallop’s value is found not just in its flavor, but also its promise for a new era of sustainable seafood.

Over the past two decades, the unassuming sea scallop has brought on a quiet revolution in East Coast fisheries, one based on cooperation among fishermen, scientists, and government managers. Thanks in large part to the scallop, New Bedford ranks as the country’s number one fishing port (in terms of value) since 2000, landing an average of $400 million per year. This economic boost comes as stocks of several other North Atlantic species—most notably cod—are at an all-time low.

The scallop came close to sharing the cod’s dismal fate. Landings in the mid-1990s were a quarter of what they are now. In 1994, several areas of Georges Bank were closed in order to protect ground fish, a decision that left scallopers fighting over the dregs in less productive areas. The number of days each vessel was allowed at sea was slashed. From Maine to Virginia, boats sat idle at port or on the auction block.

Jesse Rose, a fourth-generation Wellfleetian, remembers those days. In 1997, at the age of 17, he joined a large commercial scallop crew out of New Bedford. By the end of the 13-day trip, the catch was so poor that he owed the captain money. It was a lesson he never forgot.

But a few years later, the National Marine Fisheries Service allowed an exploratory study in a closed area of Georges Bank and another off of Nantucket. They pulled up more scallops than anyone thought possible: 700 bushels in a 10-minute tow, recalls Ron Smolowitz, a former captain and gear designer with the Fisheries Service.

“It would have taken a vessel 40 hours of bottom time to do that outside of that area,” said Smolowitz, who now runs a non-profit research organization called the Coonamessett Farm Foundation, as well as Coonamessett Farm in Hatchville. “When the industry heard about this, the Rubicon had been crossed. I just saw that what we need to do is figure out a management regime that allows us to grow more scallops.”

Though a hardship for fishermen at the time, the closures had allowed the juvenile scallops to grow. Instead of getting 30 meats per pound, fishermen filled their cheesecloth bags with scallops twice that size. Those patty-like scallops became prized gems in fish markets, fetching over $10 to $15 per pound off the boat, and even more overseas.

Not only were scallopers reaping higher profits for their efforts, the larger, more mature scallops had been able to spawn several times in five to seven years in the closed areas, leaving a trail of juvenile seed in their wake. The Fisheries Service established six “closed areas” in New England and Mid-Atlantic waters, which opened on a rotating basis. The hunter-gatherers took a note from agriculture: by rotating the “fields”, the scallop seed could take root and grow, allowing populations and habitat to rebound, while fishermen harvested the productive areas.

“We close those ‘fields’, if you will, until they’re ready to harvest and then we open those fields and allow them to be harvested,” explains Smolowitz.

Within a short time, the scallop fishery was booming. In Provincetown and Chatham, the homeports of general category (dayboat) fishing vessels, fishermen switched from trawl fishing to scalloping. Though the days at sea and crew sizes were limited, the money was good enough to live on all year.

By the mid-2000s, Rose had been on commercial vessels for a decade, fishing for everything from surf clams to yellowfin tuna. But as a father, he wanted to find a way to make a living while still living at home. So he bought his first boat, christened it Midnight Our, and started fishing for scallops out of Wynchmere Harbor.

Luckily for Rose, he got into scalloping during some “banner years” just off of Chatham. On his first tow on the new boat, he remembers filling the hatch within eight minutes of towing. Times aren’t always so easy for dayboat fishermen, who compete with larger boats for scallops in near-shore areas. In recent years, the Cape fleet has been lured to more fertile fishing grounds in the Mid-Atlantic, but Rose opted not to join them.

“I love my family. The money in [off-shore] scalloping is great, but it doesn’t buy everything,” says Rose, who plans to try his luck closer to home this winter.

**

As the value of the scallop fishery has increased, so has the investment in research. Taking notice of the positive impacts of science-based management, leaders of the scallop fleet formally pooled their resources in 2001 to create the nation’s first research set-aside program (RSA). By “setting aside” the sale of 1.25 million pounds of scallops a year—an average of $12 million—the industry funds studies on everything from gear efficiency to bycatch reduction, as well as surveys along the entire Eastern seaboard.

“The research has been a tremendous help,” says Rose, who as a general category fisherman can access the study results, even though he doesn’t directly contribute to them. “It’s incredible what they do. They can find the scallops, count them, and protect them.”

RSA program studies—conducted by independent research institutions and overseen by the New England Fisheries Management Council—give the scallop fleet the equivalent of a second opinion on the government’s surveys. After extensive discussion and review, the findings of RSA studies have led to new regulations—the bane of fishermen’s existence. But now there’s a difference. The fishing community understands and accepts the regulations because they have taken part in the research, whether by bringing scientists out to sea or contributing their catch and personal observations.

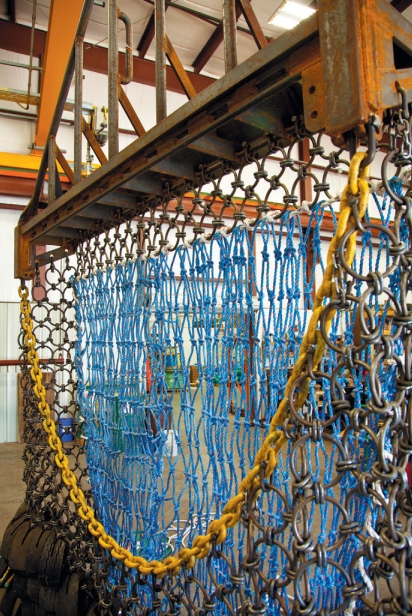

To the outside observer, the changes brought about by the RSA program are mostly cosmetic. The scallop dredge was modified to only let scallops larger than four inches through the rings, leaving the smaller ones to grow. The regulations called for larger spacing in the dredge’s twine top to allow flounder and other non-target species to escape. And most crucially, the dredge was redesigned to prevent sea turtles from entering or getting hit.

Sea turtles are threatened or endangered all around the world, and loggerheads in the North Atlantic are no exception, partially due to interactions with fishing vessels. According to Smolowitz, over 700 turtles a year were reported dead or injured by scallopers in the early 2000s. As a result, sea scallops were flagged as “seafood to avoid” on watchlists compiled by Greenpeace and the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

After dredge modifications developed by the Coonamessett Farm Foundation became mandatory, reports of sea turtle deaths or injuries were rare. Due in large part to the gains achieved through the RSA program, the internationally-recognized Marine Stewardship Council certified Atlantic sea scallops as a sustainable fishery in 2013.

**

For many people, “sustainability” is a loaded word. For fishermen like Rose, it means diversifying his target species so that he can fish year-round and sell the catch locally.

“I love providing fish—a wonderful, viable resource—to people. It’s great to feed your community,” Rose says. “I take pride in keeping it on the Cape.” He currently sells live or shucked scallops directly to Mac’s Seafood on the Lower Cape and Hatch’s Fish Market in Wellfleet, and is working on a deal to supply Whole Foods.

For Smolowitz, sustainability means improving technology and market share for small-scale fishermen and farmers.

“I personally believe that we need to have decentralized food production. So instead of going with large corporate farms or depending on large foreign factory fleets, we should have small scale, localized food production,” he says.

“Technology allows us to manage in a more sustainable way. It allows us to conduct the research that we need to make the right decisions; it allows us to do the gear design work that we need to do to appropriately harvest the right size animals without causing any harm to any other animals or environment. So technology is the key.”

And for many consumers, sustainability signifies a guilt-free purchase. One way to ensure that you’re eating sustainably-managed seafood is by buying local and asking questions about the source of your food, says Nancy Civetta of the Cape Cod Commercial Fishermen’s Alliance.

“So much seafood landed on Cape Cod is shipped over the bridge or overseas. The bottom line in changing that is increasing the seafood eaten by Cape Codders,” Civetta says. “Each of us living on Cape Cod should ask if fish is from local waters and supports our local industries.”